|

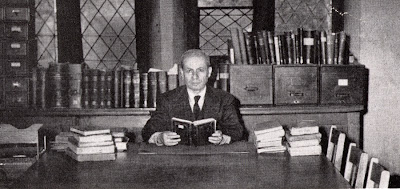

| Philip K. Hitti at Princeton |

|

| Hitti |

Hitti wrote many other books, on Lebanon, Syria, and much else; for a long time he was the only Middle Eastern scholar writing in the US in English on Middle Eastern history (though he was soon joined by Aziz Atiya and other pioneers). He was a man of his times; some of his books on Lebanon dwell a bit awkwardly on trying to interpret the "racial" characteristics of Maronites, Druze, and others. (A friend, himself a distinguished historian today, once privately told me Hitti spent too much time "measuring noses.") But that is a product of his era. Hitti was a founding father. Without him, and without History of the Arabs, the whole Arab Studies field would look quite different today. Medicine has outgrown Galen, and mathematics has outgrown Euclid; so in the light of today's Arabic Studies literature, Hitti's work seems old-fashioned, stuffy, and incomplete. But if we see farther today, as the cliche goes, it is because we stand on the shoulders of giants, and in the US Arab Studies community, the man at the bottom of that inverted pyramid is Philip Hitti.

I am told that there is, or was, a Lebanese cedar growing at Princeton, where Hitti taught for decades, because he had brought it over from Lebanon. Cedars can live a thousand years; may it do so. Seventy-five years since History of The Arabs first appeared and nearly 35 years after his death, we still owe much to Hitti, who brought much more than that cedar to this country.

No comments:

Post a Comment