|

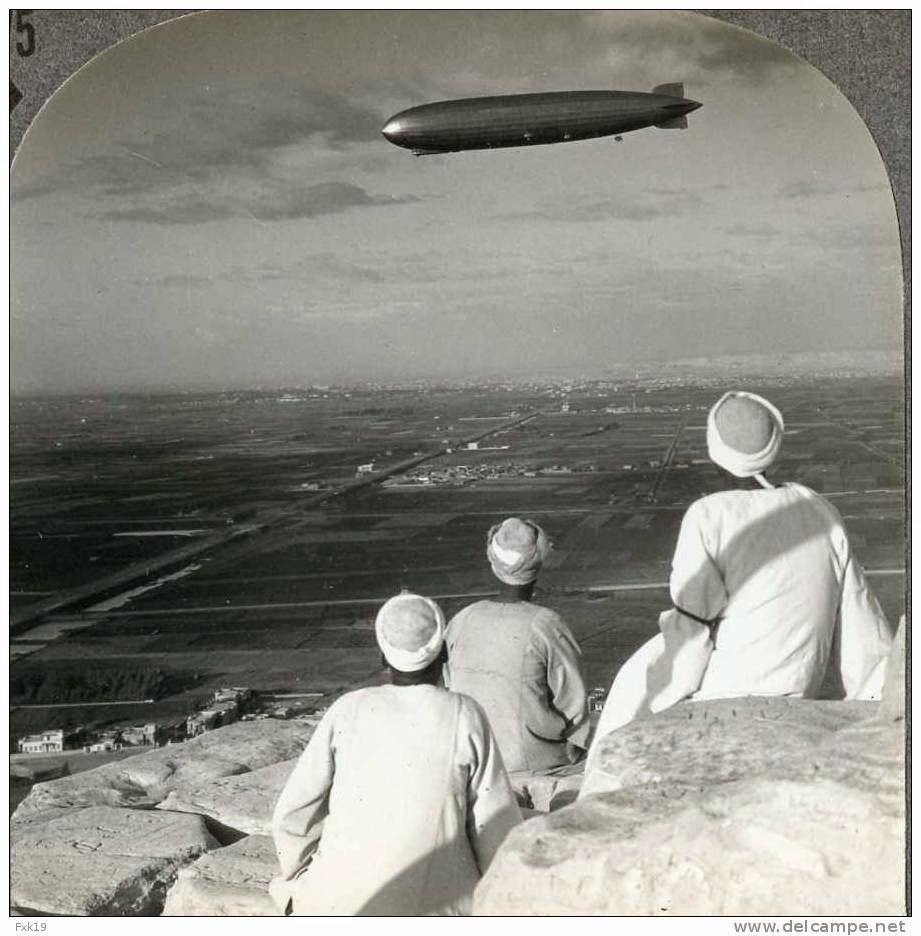

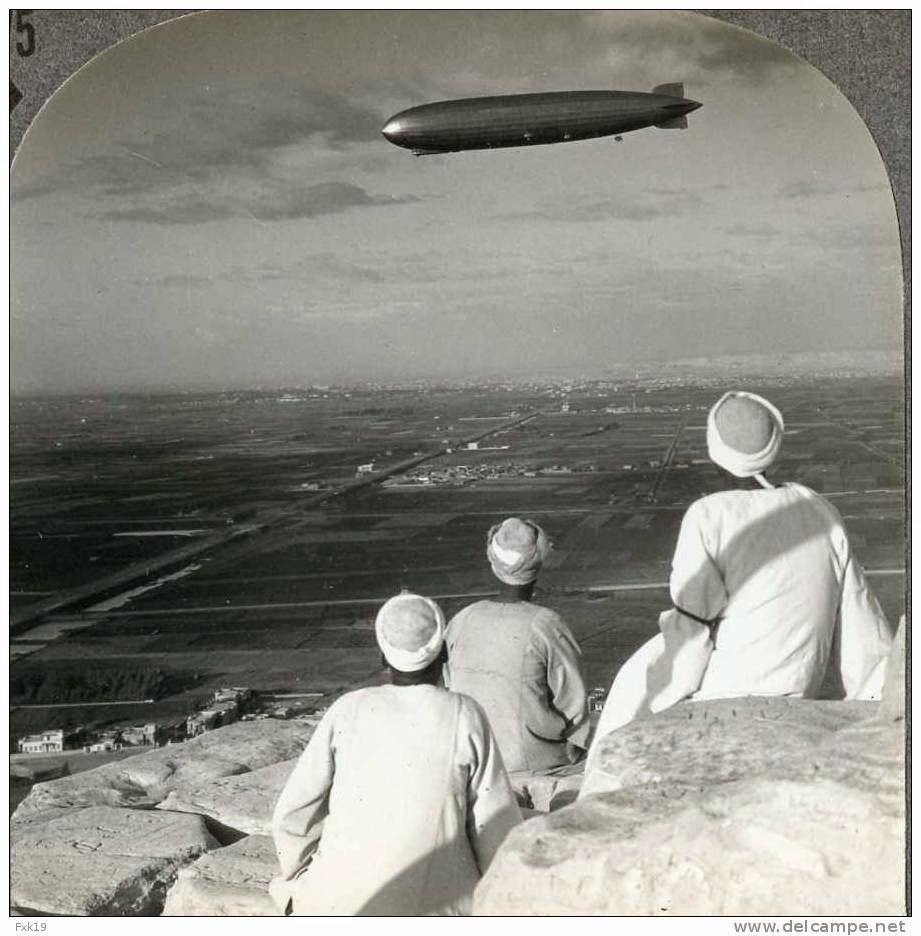

| Graf Zeppelin at the Pyramids, 1931 |

(This replaces an earlier version of this post which was corrupted.)

The great age of luxury Zeppelin travel was a brief one in the 1920s and 1930s, memorably concluding with the

Hindenburg disaster in 1937. The rigid dirigible airship, designed by Count (

Graf in German) Ferdinand von Zeppelin in the 1890s, originally was used for military applications through World War I; Count von Zeppelin died in 1917,and the Zeppelin company was taken over by Dr. Hugo Eckener. Barred by the Versailles Treaty from building military Zeppelins, Eckener eventually won the right to build Zeppelins for civilian transport, and created the idea of these luxury liners of the sky for European and American elites, that could carry people across the Atlantic in comfort faster than a ship, at a time when heavier-than air aircraft were not yet ready to carry passengers so far.

Dr. Eckener's gem was the

Graf Zeppelin, named for Count von Zeppelin and intended to demonstrate the Zeppelin's capabilities as the airborne version of a luxury liner. As the Weimar Republic struggled to recover from World War I, she became a major showpiece for the reputation of German aeronautical engineering. Later that year she made her first Transatlantic trip, to the US. She would make other high-profile flights, including a round-the world-flight in 1929, but here I wish to discuss her two visits to the Middle East, in 1929 and 1931.

But those trips, including photos, will appear in Part II of this post. Here in Part I, I want to discuss military Zeppelins in the Middle East.

Earlier Zeppelins in the Region

But first, a few words about military Zeppelin use in the Middle East prior to the golden age of luxury Zeppelin travel.

During the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-1912, Italy became not only the first country to drop an aerial bomb from a heavier than air airplane, but probably also the first to use dirigibles for bombing. (Some use "Zeppelin" for all rigid dirigible airships, others only for the German products).

|

| Italian Dirigible Bombing in Libya |

During the bombing of Libya in 2011

I noted this on this blog, and posted this photo of Italian dirigibles dropping bombs on Turkish positions in Libya.

L59: "Das Afrika-Schiff"

At least as far as I am aware, the next use of a Zeppelin over the Middle East was an abortive German attempt to relieve its beleaguered forces in German East Africa (Tanganyika, now the continental part of Tanzania) during World War I. General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck's force in German East Africa was caught between British forces in Kenya and South African forces under General Jan Smuts. (Film buffs may note that this campaign is the context of the great, fictional, Bogart-Hepburn movie

The African Queen.)

Determined to resupply their forces n East Africa, the Germans sent Zeppelin L59 to Bulgaria (a German ally) in November 1917. Its ambitious mission was to overfly British-occupied Egypt and Sudan without being detected, carrying some 25 tons of weapons and supplies to von Lettow-Vorbeck's

Schutztruppe. Because hydrogen would be unavailable in East Afrika, it was intended to dismantle her there, cannibalizing her parts to supply troops, including making her skin into tents. (The narrative which follows is based on numerous published and online accounts of the mission.)

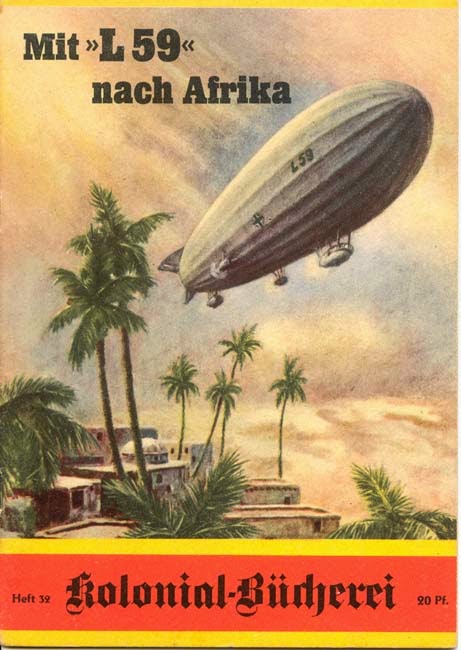

|

| Postwar German Brochure |

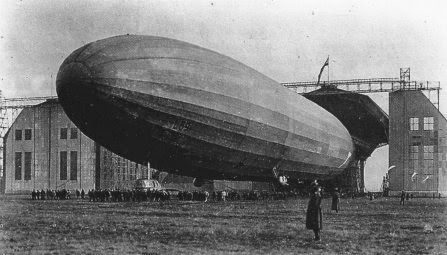

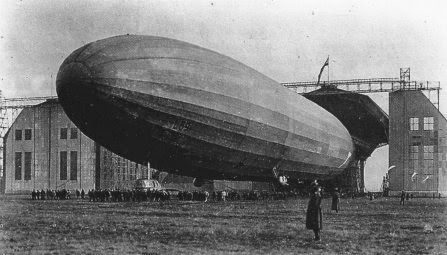

It would be a dangerous mission: her top speed would be only 50 mph, making her a sitting duck for British fighters based in Egypt, Sudan, or Kenya. The Zeppelin, whose production designation from the Zeppelin works was LZ 104, was redesignated the L59 in German Naval service. Her sister ship, L57, had originally been chosen for the Africa flight, but crashed and burned during trials.

The Zeppelin works' Dr. Eckener himself piloted her to Jamboli airfield in Bulgaria, a German ally, where command was handed over to KapitanLeutnant (Lieutenant Commander) Ludwig Bockholt of the German Navy.

|

| Ludwig Bockholt |

Bockholt, earlier in 1917, had drawn attention when, in command of Zeppelin L23, he had lowered a prize party from the Zeppelin to capture the Norwegian sailing ship

Royal, still the only incidence in history in which a Zeppelin captured a surface ship. So he may have seemed the right man for a daring mission.

|

| Zeppelin LZ 104/L59 |

After two false starts,she took off on November 21, 1917. She passed across Turkish airspace (allied with Germany) and headed out over the Mediterranean. Over Crete she encountered a thunderstorm and, as was standard practice, retracted her radio antenna to avoid lightning strikes. Meanwhile in East Africa, von Lettow-Vorbeck had suffered a defeat and was withdrawing into rough terrain where the Zeppelin could not land (he eventually crossed into Portuguese East Africa/Mozambique. The German Colonial Office tried to recall the L59 but with her antenna retracted she missed the signal.

|

| Route of L59 in Africa and After |

At 5;15 AM on November 22, L59 crossed the African coast near Mersa Matruh. As the morning sun heated the Sahara below, the airship experienced considerable turbulence; the heat of the days and bitter cold of the desert nights also affected the crew adversely, some even experiencing hallucinations.

She passed over the Farafra and Dakhla oases on course to parallel the Nile from Wadi Halfa. On that afternoon, however, her forward engine seized up. She continued to make good time on her remaining engine, but the forward engine controlled the power to her radio transmitter, so she was from that point on unable to transmit, though she could receive with some difficulty.

While the loss of the transmitter made it impossible to contact Germany, it may have had another benefit: British Intelligence knew the Germans planned to make the attempt, but were unsure of the timing; British fighters in Egypt and stations in Sudan and Kenya were ordered to watch for and intercept her, and were listening for her radio transmissions. Her inadvertent radio silence may have helped her evade detection.

Sundown on the 22nd found L59 over Sudan; she had reached the Nile and was following it southward. the sharp drop in desert temperatures at night caused her hydrogen bags to lose buoyancy and she lost altitude.

At 12:45 AM on the 23rd, L59 finally received the German recall order. There was some debate as some preferred to go on, but Holbock decided to turn back. Meanwhile, about 3 am, her loss of buoyancy due to the cold caused her to stall and nearly crash in the desert, but control was regained.

Finally, about 125 miles west of Khartoum, L59 turned around and headed for home.he had passed over Egypt and half of Sudan, and now had to pass over them again without being detected.

There has been some controversy over the recall message. British Intelligence operative Richard Meinertzhagen would claim that it was a British ruse, broadcast in German naval code and claiming von Lettow-Vorbeck had surrendered. The British may have transmitted recall messages (though days later they were still looking for Zeppelin in East Africa, so they apparently did not know where it was. The recall message was not about a surrender, but a retreat, and the message recorded in L59's log reportedly matches the one sent by the German Navy. Meinertzhagen's recent biographers have called into question his once famous diaries, which appear to be full of fabrications.

L59 successfully avoided detection and reached the Mediterranean. She was not quite home free, having another loss of altitude after night fell and nearly crashed in western Turkey, which was at least friendly ground, but recovered, and landed back at Jamboli at 7:45 am on November 25. She had flown for 95 hours and 4,200 miles without landing, a Zeppelin record that would stand until the great ocean-crossing passenger Zeppelins of the 1920s and 1930s.

Since the original plan was to dismantle L59 once in Africa, and with Lettow-Vorbeck now in Mozambique, the Germans had no immediate plans for L59, so they decided to modify it to carry bombs and keep it in the Mediterranean theater. On March 11-12, 1918, she raided Italy, bombing Naples.

Its next mission was an attempt to bomb Port Said and the Suez Canal.later in March reached a point about three miles from the target, when contrary winds forced a retreat. Unfavorable winds also forced abandoning the backup target, Suda Bay in Crete.

On April 7, 1918, L59, still commanded by Bockholt, took off from Jamboli to bomb the British base at Malta. She crossed the Straaits of Otranto and headed towards Malta. The German submarine UB-53, running on the surface, witnessed her passing low overhead; the U-Boat commander estimated her altitude at 210 meters and reported he could see the details of the Gondola.

A bit after the Zeppelin passed over, the U-Boat commander reported hearing two explosions and then witnessing a giant flame descending into the sea. She was listed as lost to an accident since neither the Italians nor the British claimed to have brought her down; none of the crew of 21, including Bockholt, survived.

Some in the German Navy's Zeppelin service reportedly suspected that UB-53 might have mistaken L59 for an Italian airship and shot her down, then realized their error. This is unproven, and UB-53 herself went down after hitting a mine in Otranto in August 1918.

That's the strange tale of Zeppelins in wartime in the Middle East. Tomorrow, the luxury liners of the sky era:

Graf Zeppelin's 1929 and 1931 visits to the region.

.jpg)