When the rise of the Islamic State led to extensive killings and enslavement of Yazidis (Yezidis, etc.) in 2014, the media was not only unsure how to spell it (which is in part as much about etymology as transliteration), but how to characterize the faith: is it an offshoot of Islam? A heterodox Sufi order? Are they "devil-worshippers" as many Muslims believe? Are they polytheists? A sect of Zoroastrianism? Arguments can be made that they are a little bit of all these things, but not defined by any of them. And the Yazidis are just one of a number of relic sects, mostly found in remote areas (the Kurdish or Syrian mountains, the Iraqi Marshes) where Islam largely left them alone. Most are secretive about their beliefs in part to avoid accusations of heresy. And unlike the equally varied Christians of the Middle East and the remaining Jewish populations, they have no obvious foreign patrons, other than small diasporas, to advocate for them.

There are many of these small sects, or separate religions, some with overlapping or similar beliefs, others unrelated. They range in size and prominence from the Syrian ‘Alawites, who dominate the Asad regime, and the Druze, who are prominent in Lebanon, Syria, and Israel/Palestine, to tiny groups limited to a few villages.. Both of the big sects tend to portray themselves as Muslim sects, the ‘Alawites more convincingly than the Druze.

The Middle East is a palimpsest of all the peoples and faiths that have passed through, and many have left traces. Many of these surviving small groups combine bits of extreme (ghulat) Shi‘ism, Sufi mysticism, gnostic elements of esoteric (batini) versions of Islam, ideas of emanations of the divine from Neoplatonism and orthodox and unorthodox Zoroastrianism, and concepts like metempsychosis and reincarnation. Christian elements also can be found. (Not all at once, of course.) And some, like the Mandaeans of Iraq and southwestern Iran, and the Druze, do not fit this generalization perfectly.

An example of this syncretism are the Shabak, a small ethnic group and sect found in the Mosul area. Theologically they have links to the Yazidis and the Ahl-i Haqq or Yarsanis. (No relation to the Israeli Internal Security Service known as Shin Bet or Shabak.) They make pilgrimages to both Yazidi and Shi‘ite shrines, including Najaf and Karbala. They practice a form of confession similar to Christianity. They venerate the Sufi poetry of Shah Isma‘il I, founder of the Safavid dynasty in Iran, and some historians believe they may be descendants of the Qizilbash movement that backed him.

Most speak either Kurdish or the Shabaki dialect of Gorani, itself close to Kurdish, though a few speak Arabic. Yet their holy book, the Buyruk, is written in Turkoman.

If you are confused, welcome to the club. Adding to the confusion is the fact that like similar groups, they have an elite class, the pirs, who are privy to the full secrets of the faith, not necessarily shared with the rank and file. In the days before modern anthropology, these groups were mainly known through medieval Sunni catalogs of "heresies," such as Al-Baghdadi's Al-Farq bayn al Firaq and Al-Shahrastani's Kitab al-Milal wa'l-Nihal. These interpret the sects through a Sunni lens usually beginning from the hadith that runs, "‘The Jews were divided into 71 or 72 sects as were the

Christians. My Ummah will be divided into 73 sects." But few of these groups pretend to be Sunni, so the heresiographers concentrate on refutation rather than description.

Though there is much anthropological literature out there, the inherent secrecy of these groups raises questions of reliability. And the early history and evolution of these groups remains obscure.

I want to spend as long as needed to survey as many as possible of these groups. By looking at several categories that make it easier to deal with several at a time. I see this as a long-term series to introduce these small, somewhat fossilized faiths. And I have resisted the temptation to title the series The Joy of Sects.

.

Tuesday, January 31, 2017

Monday, January 30, 2017

The New Colossus

The final five lines of Emma Lazarus' 1883 poem "The New Colossus" are engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,With conquering limbs astride from land to land;Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall standA mighty woman with a torch, whose flameIs the imprisoned lightning, and her nameMother of Exiles. From her beacon-handGlows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes commandThe air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries sheWith silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Friday, January 27, 2017

This Blog is Eight Years Old Today

On this date back in 2009, Barack Obama was a newly-inaugurated President of the United States, and I began blogging for The Middle East Institute. I've blogged my way through a lot: from Obama's Cairo speech, Arab Spring, and all the horrors since. But I'm still here, and I thank my readers and commenters as we enter our ninth year.

Wednesday, January 25, 2017

January 24, 1917: Royal Navy and Arab Revolt Take Wejh

|

| Hejaz 1917, showing the rialway and the coast from Yenbo northward |

Last year we examined the early days following the outbreak of the Great Arab Revolt in 1916. After the initial successes in capturing Mecca, Jidda (with the help of the Royal Navy), and Ta'if, advances slowed. The Hejaz Railroad at the time reached only to Medina, but that let the Ottoman forces reinforce the Medina garrison.

In the latter part of 1916, the Royal Navy aided the Sharifian forces in taking the Red Sea port towns of Rabegh and Yenbo (Yanbu‘). Late in the year, a Turkish attempt to retake the two ports was repulsed by the Sharifian Forces and the Royal Navy.

But, particularly in the first year or two of the Revolt, the British media downplayed the role the Royal Navy was playing, fearing the Turks would use it to portray the Revolt as a British-inspired rebellion (they portrayed it that way anyway, and it largely was).

|

| Lawrence at Wejh, 1917 |

By January 1917, Faisal's Army (with Lawrence in tow) was in Yenbo, sheltering under the Royal Navy's guns. Lawrence already had his orders to return to Cairo; his replacement, Stewart Newcombe, was en route to replace him.

|

| Newcombe |

Newcombe had previously served with Lawrence at Cairo, but then had left

to serve at Gallipoli. Now a colonel, he considerably outranked

Lawrence and was about to become head of the whole Military Mission to

the Hejaz. But Lawrence trusted him and they would forge a lifelong

friendship: Newcombe would be a pallbearer when Lawrence died. But

Lawrence had already delayed his return to Cairo, which wanted him back,

and he would run out of excuses when Newcombe arrived.

The decision was made to take the port town of Wejh, well to the north of Yenbo. It would give the British another supply base to support raids on the Hejaz Railway, and allow support for Sharifian operations much farther north. There was a Turkish garrison at Wejh, and the local Balli (or Billi) tribe was considered to be pro-Turkish.

Again, this could not be done without the Royal Navy. It was decided to embark weapons and a small Arab force, to advance on Wejh by sea while Faisal's Army advanced by land. They were to converge January 23rd or 24th. Lawrence would embark at Yenbo and be transported to the coastl town of Umm Lajj, midway up the coast.

The Royal Navy's Red Sea Patrol was commanded by Rear Admiral Sir R.E. Wemyss. The operational group advancing on Wejh consisted of HMS Fox, under Captain W.H.D. Boyle, who would go on to be a Fleet Admiral and the hereditary Earl of Cork in the Irish Peerage; the troopship Hardinge, with 400 Arab fighters on board, and the Espiegle, Suva, and Anne.

By January 21 the ships had set off or Wejh. Newcombe had been delayed in Cairo, which Lawrence took as a sign he should accompany Faisal to Wejh. Only hours after leaving Umm Lajj, Newcombe overtook the column. But Lawrence was in luck, since Newcombe felt he needed time to get to know Faisal, he asked Lawrence to remain with the expedition. Faisal also begged Cairo to leave Lawrence in the field, and the rest is history.

The expedition did not go as planned. The ships arrived off Wejh to find no sign of Faisal's Army. When they had still not arrived on the 24th, Boyle decided to land the troops he was carrying. The Arabs and a naval landing party who had gone ashore on the 23rd near Wejh, advanced on the town early on the 24th. The small Turkish garrison withdrew while the fight in the town continued. The Arab fighters soon descended into looting, but by the end of the day the town was secure. When Faisal and Lawrence arrived the next day, the Royal Navy had won the day. Losses were about 20 Arabs and one British officer killed, and two British seamen wounded.

Of course, the British gave credit to the Arab Revolt, and Lawrence, in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, devotes dozens of pages to a detailed discussion of the march on Wejh, and only about a page to the fact the battle was over when they got there.

Again, this could not be done without the Royal Navy. It was decided to embark weapons and a small Arab force, to advance on Wejh by sea while Faisal's Army advanced by land. They were to converge January 23rd or 24th. Lawrence would embark at Yenbo and be transported to the coastl town of Umm Lajj, midway up the coast.

|

| HMS Fox |

By January 21 the ships had set off or Wejh. Newcombe had been delayed in Cairo, which Lawrence took as a sign he should accompany Faisal to Wejh. Only hours after leaving Umm Lajj, Newcombe overtook the column. But Lawrence was in luck, since Newcombe felt he needed time to get to know Faisal, he asked Lawrence to remain with the expedition. Faisal also begged Cairo to leave Lawrence in the field, and the rest is history.

The expedition did not go as planned. The ships arrived off Wejh to find no sign of Faisal's Army. When they had still not arrived on the 24th, Boyle decided to land the troops he was carrying. The Arabs and a naval landing party who had gone ashore on the 23rd near Wejh, advanced on the town early on the 24th. The small Turkish garrison withdrew while the fight in the town continued. The Arab fighters soon descended into looting, but by the end of the day the town was secure. When Faisal and Lawrence arrived the next day, the Royal Navy had won the day. Losses were about 20 Arabs and one British officer killed, and two British seamen wounded.

Of course, the British gave credit to the Arab Revolt, and Lawrence, in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, devotes dozens of pages to a detailed discussion of the march on Wejh, and only about a page to the fact the battle was over when they got there.

January 25, 2011: The View Six Years Later

How the world has changed in six years. On this day in 2011, what became the Egyptian Revolution began, fresh on the heels of the successful revolution in Tunisia. How remote those heady days seem. The military that claimed to intervene in support of the revolution today rules the country. Syria is destroyed, Libya and Yemen profoundly divided, and only Tunisia has successfully experienced a peaceful transfer of power after elections. It is easy to assume "Arab Spring" was a failure, but that assumes that it has run its course. I am not so sure. Demand for change may have abated, but it has not ended. Many voices for democratic change have been silenced by arrest or exile, and many ordinary citizens have been persuaded that change is destabilizing, but the seeds once planted may yet spring to life again. Egypt and Bahrain in particular may be "stable," but Egypt's economy is severely challenged, dependent on foreign cash.

History takes place over the long run. The first flowering of Arab Spring failed, except for Tunisia. A second flowering may be long delayed, and new models of democratic reform less dervative of Western models may emerge. Or, of course, I could be just an incurable optimist.

History takes place over the long run. The first flowering of Arab Spring failed, except for Tunisia. A second flowering may be long delayed, and new models of democratic reform less dervative of Western models may emerge. Or, of course, I could be just an incurable optimist.

Wednesday, January 18, 2017

The Wilder Shores of Machine Translation: "the Field of Youth Creationism Doritos Taha"

I never use Facebook's built-in translation function unless friends are posting in a language I don't know, but sometimes it seems to translate automatically, not always with the best results:

The second part almost approaches comprehensibility, but "Joey scene appears in the field of youth creationism doritos taha masjid yusuf aga time" is a sublime victory for computer translation running off the rails.

The second part almost approaches comprehensibility, but "Joey scene appears in the field of youth creationism doritos taha masjid yusuf aga time" is a sublime victory for computer translation running off the rails.

The photo accompanying it is this:

Now let's look at what the caption really says: "Cairo: aerial view of Bab al-Khalq Square; in the midst of it is the Mosque of Yusuf Agha, the Governorate Building, and the Dar al-Kutub (National Library), and the Islamic Museum. At the top of the picture appears Abdeen Palace and the area surrounding it . . . Picture from the thirties of the last century."

It leaps the rails at the beginning, when "aerial view" becomes "Joey scene," though the word for aerial (jawiyy) has clearly been read as "Joey." The square in question, Bab al-Khalq, can be translated as "Gate of the People," or the "Masses," but Khalq can also mean "creation," so I guess that explains "creationism." I don't know where "youth" came from. Any ideas? But the real genius was turning one word in Arabic, يتوسطه, into two, "doritos taha." If you ignore the actual voweling, you might come up with "itostaha," quite wrongly, but the "do-" is nowhere to be found.

The second part almost approaches comprehensibility, but "Joey scene appears in the field of youth creationism doritos taha masjid yusuf aga time" is a sublime victory for computer translation running off the rails.

The second part almost approaches comprehensibility, but "Joey scene appears in the field of youth creationism doritos taha masjid yusuf aga time" is a sublime victory for computer translation running off the rails.The photo accompanying it is this:

Now let's look at what the caption really says: "Cairo: aerial view of Bab al-Khalq Square; in the midst of it is the Mosque of Yusuf Agha, the Governorate Building, and the Dar al-Kutub (National Library), and the Islamic Museum. At the top of the picture appears Abdeen Palace and the area surrounding it . . . Picture from the thirties of the last century."

It leaps the rails at the beginning, when "aerial view" becomes "Joey scene," though the word for aerial (jawiyy) has clearly been read as "Joey." The square in question, Bab al-Khalq, can be translated as "Gate of the People," or the "Masses," but Khalq can also mean "creation," so I guess that explains "creationism." I don't know where "youth" came from. Any ideas? But the real genius was turning one word in Arabic, يتوسطه, into two, "doritos taha." If you ignore the actual voweling, you might come up with "itostaha," quite wrongly, but the "do-" is nowhere to be found.

Labels:

Arabic language,

Cairo,

Egypt,

humor,

translation

Tuesday, January 17, 2017

The Battle of Rafah, January 9, 1917: Part II, New Zealand Wins the Day

In Part I of this post last week, we discussed the lead-in to the final move in the Sinai Campaign, through the Battle of Magdhaba in late December 1916. After the surrender of the Ottoman position at Magdhaba, the main remaining Ottoman position inside Egyptian Sinai was at Rafah, then as now right on the border with what was then Ottoman Palestine.

As January 1917The British knew from aerial reconnaissance that 2000 to 3,000 Ottoman and German troops were entrenched at Magruntein southeast of Rafah and others massing around the border. Meanwhile German aircraft bombed British troops at El ‘Arish.

The Allied Forces in Sinai constituted the Desert Column, under the command of Gen. Philip Chetwode, based at El ‘Arish.

The main operational force, as at Magdhaba, would be the ANZAC Mounted Corps, consisting of three brigades of Australian Light Horse and a New Zealand Mounted Rifle Division, all under the command of Harry Chauvel, a Queensland soldier who would prove to be the first Australian full general and probably the most famous cavalryman of World War I.

The ANZACs advanced overnight and discovered the enemy strongly entrenched in country that was generally open and without cover. Using similar tactics to Magdhabs, relying on the mobility of the Light Horsemen, tje ANZACs sought to surround the Turkish fortifications and then, fighting dismounted, to attack their positions. But dismounted cavalry may have great mobility but provide a weak line fighting dismounted, and throughout much of the day, Chauvel's men were repeatedly driven back by the Turkish redoubts.

As the battle continued, Chetwode became aware that significant Turkish reinforcements numbering 2500 or more were advancing from Gaza.

Without going into extreme tactical detail, the British Empire forces had a hard slog. German aircraft were bombing them, while Australian aircraft provided recon and target spotting. In this open desert country, air power really showed its usefulness. By afternoon, reports of the approach of Ottoman reinforcements and stubborn resistance led Chetwode, who was not on the battlefield, telephoned an authorization for retreat and withdrawal.

The decision to withdraw, however, came while the 1st New Zealand Mounted Rifles and the Imperial Camel Corps were on the offensive. The New Zealanders, under the command of Gen. Edward Chaytor, decided to delay withdrawal until the current offensive played out.

Attacking from the north in a bayonet charge as the Camel Corps attacked elsewhere, the New Zealanders managed to seize the Central Redoubt of the Ottoman position, and the resistance began to collapse. In the process, the Kiwis achieved another distinction: by swinging northeast beyond the Ottoman border, they could claim to have initiated the Palestine Campaign at the moment they were ending the Sinai Campaign.

Rafah was a small action, but it came to conventionally maek the end of the Sinai Campaign and the overture to the Palestine Campaign. Below, a hand-drawn map from 1917.

As January 1917The British knew from aerial reconnaissance that 2000 to 3,000 Ottoman and German troops were entrenched at Magruntein southeast of Rafah and others massing around the border. Meanwhile German aircraft bombed British troops at El ‘Arish.

|

| Chetwode (in front), El ‘Aris, Jan.1917 |

|

| Harry Chauvel |

The ANZACs advanced overnight and discovered the enemy strongly entrenched in country that was generally open and without cover. Using similar tactics to Magdhabs, relying on the mobility of the Light Horsemen, tje ANZACs sought to surround the Turkish fortifications and then, fighting dismounted, to attack their positions. But dismounted cavalry may have great mobility but provide a weak line fighting dismounted, and throughout much of the day, Chauvel's men were repeatedly driven back by the Turkish redoubts.

|

| Firing line at Rafah |

|

| Chaytor |

Attacking from the north in a bayonet charge as the Camel Corps attacked elsewhere, the New Zealanders managed to seize the Central Redoubt of the Ottoman position, and the resistance began to collapse. In the process, the Kiwis achieved another distinction: by swinging northeast beyond the Ottoman border, they could claim to have initiated the Palestine Campaign at the moment they were ending the Sinai Campaign.

Rafah was a small action, but it came to conventionally maek the end of the Sinai Campaign and the overture to the Palestine Campaign. Below, a hand-drawn map from 1917.

Monday, January 16, 2017

Yannayer: Belated Berber New Year

This has been the three day Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday here in the US, and as a result I am late in wishing Amazigh Berber readers a happy new year according to the old (Julian) agricultural calendar on January 14.

This has been the three day Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday here in the US, and as a result I am late in wishing Amazigh Berber readers a happy new year according to the old (Julian) agricultural calendar on January 14.I've talked about Yannayer several times in previous tears, While the Julian date for the New Year is an ancient one in North Africa, celebrating it has become more popular with revival of Amazigh pride and identity in recent years. As I have noted before, the so-called Berber era, dating from 950 BC, is a modern nationalist invention; by that reckoning this is the year 2962, As I also noted in a previous post, while January 14 is the correct date of the Julian New Year, some Algerian Imazighen celebrate on January 12 instead.

Wednesday, January 11, 2017

The Battle of Rafah, January 9, 1917: Last Ottomans Pushed Out of Sinai, Part I

Journal deadlines and other news have delayed this post, which really should have appeared two days ago. Last summer we traced the Ottoman Army's second advance toward the Suez Canal, and its ultimate repulse at the Battle of Romani in August of 1916.

During the remainder of the year, the British Empire Forces (mostly ANZACs). The advance was slowed by the need to build the railroad line and a pipeline for water forward as they moved. Finally, in two actions in eastern Sinai in December 1916 and January 1917, the last Ottoman troops were pushed out of Egyptian territory. With the Battle of Rafah a century ago Monday, British war historians mark the end of the Sinai Campaign.

The Main Allied force was rhe ANZAC Mounted Division, consisting of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Australian Light Horse Brigades and a New Zealand Mounted Rifle Division. From December 1916 these forces were assigned to the Desert Column, formed to support operations in Sinai and Palestine.

On December 20, 1916, the Allied force reached El ‘Arish, where they discovered the Ottoman force had evacuated the town and withdrawn up the Wadi El ‘Arish to the vicinity of Magdhaba to the southeast. (See map above. Illustrations are from Wikimedia.) Unwilling to advance beyond El rish while leaving Turkish and German forces behind their right in a fortified position at Magdhaba (not far from the big Turkish support base at Hafr al-‘Auja, just inside the Palestinian side of the border).

The Commander of the Desert Column, Sir Phillip Chetwode, arrived at El ‘Arish with supplies from Port Said, and prepared to dispatch the ANZACs under Sir Harry Chauvel. The German Commander of the Ottoman Desert Force, Kress von Kressenstein, had constructed a series of fortified redoubts at Magdhaba which he thought could resist attack, but he reckoned without the high mobility of the Light Horsemen.

The ANZACS, under Sir Harry Chauvel, advanced on the night of December 22-23, and in a fierce battle on the 23rd succeeded after a day's hard fighting, forced an Ottoman surrender. The fight at Magdhaba had set the stage for the Battle at Rafah, the last act in Sinai.

|

| Extending the railway across Sinai |

The Main Allied force was rhe ANZAC Mounted Division, consisting of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Australian Light Horse Brigades and a New Zealand Mounted Rifle Division. From December 1916 these forces were assigned to the Desert Column, formed to support operations in Sinai and Palestine.

|

| Turkish base at Hafr al-‘Auja |

The Commander of the Desert Column, Sir Phillip Chetwode, arrived at El ‘Arish with supplies from Port Said, and prepared to dispatch the ANZACs under Sir Harry Chauvel. The German Commander of the Ottoman Desert Force, Kress von Kressenstein, had constructed a series of fortified redoubts at Magdhaba which he thought could resist attack, but he reckoned without the high mobility of the Light Horsemen.

The ANZACS, under Sir Harry Chauvel, advanced on the night of December 22-23, and in a fierce battle on the 23rd succeeded after a day's hard fighting, forced an Ottoman surrender. The fight at Magdhaba had set the stage for the Battle at Rafah, the last act in Sinai.

Labels:

ANZACs,

Australia,

First World War,

Germany,

New Zealand,

Ottoman Empire,

Sinai,

Turkey,

UK

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

Remembering Reporter Clare Hollingworth, 1911-2017

Veteran British foreign correspondent Clare Hollingworth died today in Hong Kong at the age of 105. (Yes, 105.) Almost all the obituaries will lead with her famous scoop of being the first reporter to report the German invasion of Poland in 1939, though at the time she had been working for the Daily Telegraph only three days. Admittedly, when your first big story is breaking news of the outbreak of World War II, that can be hard to top. But she spent her incredibly long career reporting from hot spots around the world, including the Middle East. She covered the North Africa campaign, the Palestine conflict (including the bombing of the King David Hotel), covered the Algerian War of independence, reported the defection of Kim Philby, and interviewed the Shah. So she deserves being remembered on this blog for her Middle Eastern reporting, mostly from the 1940s through the 1960s.

I had the honor of knowing and occasionally working with Clare back in the 1980s, though in Europe and East Asia, not in the Middle East. At the time she made her home mostly in Hong Kong, where she spent the rest of her life, but also kept a place in Paris. I remember visiting her during the Paris Air Show one year, but I particularly remember her role as my guide on my first visit to Hong Kong in 1987.

Hong Kong was still British in those days, and was also still a key listening post for Western intelligence services keeping an eye on the mainland; as well as a Chinese intelligence listening post to the outside, the station thinly disguised as the Xinhua News Agency. Clare knew them all.

Clare must have had a home somewhere, but she seemed to live to all intents and purposes at the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents' Club, where she held court, a celebrity among her colleagues. The Club is a legend in its own right, and at the time I had recently read John Le Carre's The Honourable Schoolboy, in which the Club played a key role. Asked to introduce me to Hong Kong, Clare set up a withering schedule of meetings and interviews, often at the club. She would have been 76 at the time, and I was not yet 40, but she easily left me in her dust.

I understand five years ago, when Clare turned a mere 100, the Foreign Correspondents' Club held her a suitable party, and she still survived another five years. They don't make them like Clare anymore. RIP.

I had the honor of knowing and occasionally working with Clare back in the 1980s, though in Europe and East Asia, not in the Middle East. At the time she made her home mostly in Hong Kong, where she spent the rest of her life, but also kept a place in Paris. I remember visiting her during the Paris Air Show one year, but I particularly remember her role as my guide on my first visit to Hong Kong in 1987.

Hong Kong was still British in those days, and was also still a key listening post for Western intelligence services keeping an eye on the mainland; as well as a Chinese intelligence listening post to the outside, the station thinly disguised as the Xinhua News Agency. Clare knew them all.

Clare must have had a home somewhere, but she seemed to live to all intents and purposes at the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents' Club, where she held court, a celebrity among her colleagues. The Club is a legend in its own right, and at the time I had recently read John Le Carre's The Honourable Schoolboy, in which the Club played a key role. Asked to introduce me to Hong Kong, Clare set up a withering schedule of meetings and interviews, often at the club. She would have been 76 at the time, and I was not yet 40, but she easily left me in her dust.

I understand five years ago, when Clare turned a mere 100, the Foreign Correspondents' Club held her a suitable party, and she still survived another five years. They don't make them like Clare anymore. RIP.

Monday, January 9, 2017

‘Ali Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani,1934-2017

‘Ali Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani, the Iranian President from 1989-1997, and who held almost every other senior executive position other than Supreme Leader at one time or another, has died at age 82. Though his political fortunes have waxed and waned in recent years, he remained one of the most familiar faces throughout the entire period since the 1979 Revolution.

Born in a village near the pistachio-producing city of Rafsanjan, to a large and wealthy family which made its fortune in pistachios, The family name was Hashemi-Behramani; Rafsanajni was added as a clerical appellation. During and after his Speakership and Presidency, several of his children and siblings achieved prominence as well.

He came to be known as a moderate in the spectrum of Iranian revolutionaries; he had traveled in the United States before the Revolution.

At the seminary in Qom, he became a disciple of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. When Khomeini was forced into exile, he represented him as a leader in the domestic opposition to the Shah. After the Revolution he was a prominent figure in the Revolutionary Council, served as Minister of the Interior, as Tehran Friday Prayer Imam, and was Speaker of Parliament from 1980 to Khomeini's death in 1989. He served as a member of the Council of Experts from 1983 until his death, and as its Chairman 2007-2011.

As Khomeini's Personal Representative to the Supreme Defense Council he also served as Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, he essentially was in command during the last year of the Iran-Iraq War, and accepted its end.

From early 1989 until his death he also chaired the powerful Expediency Discernment Council.

When Khomeini died in 1989, President ‘Ali Khamene'i was chosen as the new Supreme Leader, and Rafsanjani ran for and won election as Iran's fourth President. He improved relations with the outside world, including Saudi Arabia.

After the Presidential years he remained influential, remaining on the Council of Experts until replaced in 2011, and as Chairman of the Expediency Council until his death. In 2013 he registered to run for the Presidential elections, but was disqualified by the Council of Guardians. He then backed the election of Hassan Rouhani.

Rafsanjani reportedly died of a heart attack.

Born in a village near the pistachio-producing city of Rafsanjan, to a large and wealthy family which made its fortune in pistachios, The family name was Hashemi-Behramani; Rafsanajni was added as a clerical appellation. During and after his Speakership and Presidency, several of his children and siblings achieved prominence as well.

He came to be known as a moderate in the spectrum of Iranian revolutionaries; he had traveled in the United States before the Revolution.

At the seminary in Qom, he became a disciple of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. When Khomeini was forced into exile, he represented him as a leader in the domestic opposition to the Shah. After the Revolution he was a prominent figure in the Revolutionary Council, served as Minister of the Interior, as Tehran Friday Prayer Imam, and was Speaker of Parliament from 1980 to Khomeini's death in 1989. He served as a member of the Council of Experts from 1983 until his death, and as its Chairman 2007-2011.

As Khomeini's Personal Representative to the Supreme Defense Council he also served as Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, he essentially was in command during the last year of the Iran-Iraq War, and accepted its end.

From early 1989 until his death he also chaired the powerful Expediency Discernment Council.

When Khomeini died in 1989, President ‘Ali Khamene'i was chosen as the new Supreme Leader, and Rafsanjani ran for and won election as Iran's fourth President. He improved relations with the outside world, including Saudi Arabia.

After the Presidential years he remained influential, remaining on the Council of Experts until replaced in 2011, and as Chairman of the Expediency Council until his death. In 2013 he registered to run for the Presidential elections, but was disqualified by the Council of Guardians. He then backed the election of Hassan Rouhani.

Rafsanjani reportedly died of a heart attack.

Friday, January 6, 2017

Greetings for Armenian Christmas Today, and Orthodox Christmas Tomorow

In the Middle East, Christmas is a gift that keeps on giving. Christmas doesn't come just once a year but up to four times depending on how ecumenical you want to be. The Armenian churches outside the Holy Land celebrate on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6. (Except in the Holy Land when they mark it in the Julian calendar.) Merry Christmas to those celebrating.

Most of the Orthodox Christian Churches, Oriental Orthodox, and the Church of the East celebrate Christmas on December 25 in the Julian Calendar, which currently equates to January 7 in the Gregorian, so a Merry Christmas to them tomorrow.

Fear not: it's still not over. Armenians in Jerusalem and Bethlehem will celebrate on August 18-19, Epiphany (known to Eastern churches as the Theophany) under the Julian calendar.

Most of the Orthodox Christian Churches, Oriental Orthodox, and the Church of the East celebrate Christmas on December 25 in the Julian Calendar, which currently equates to January 7 in the Gregorian, so a Merry Christmas to them tomorrow.

Fear not: it's still not over. Armenians in Jerusalem and Bethlehem will celebrate on August 18-19, Epiphany (known to Eastern churches as the Theophany) under the Julian calendar.

Labels:

Armenia,

Christmas,

Middle Eastern Christians

Thursday, January 5, 2017

1970s Activist Melkite Archbishop Hilarion Capucci Dies at 94

Melkite Catholic Patriarchal Vicar Emeritus Archbishop Hilarion Capucci, who made headlines in 1974 when Israel arrested him for supplying arms to the Palestine Liberation Organization, died January 1 in Rome. Born in Aleppo in 1922, he was arrested in August 1974 by Israel, charged with using his Mercedes sedan to smuggle arms into the Occupied West Bank. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison, but was freed after Vatican intervention and expelled by Israel in 1978.

Lionized by many Arab countries, he remained an activist for Palestinian and other causes. He was active during the Iran hostage crisis in 1979-80, negotiating the repatriation of US soldiers killed at Deser One, but was unsuccessful in negotiating the release of the Embassy hostages. In 2010 he was a passenger on the Mavi Marmara protest ship headed for Gaza when it was seized by Israel; he was held brieffly by Israel and then expelled.

Lionized by many Arab countries, he remained an activist for Palestinian and other causes. He was active during the Iran hostage crisis in 1979-80, negotiating the repatriation of US soldiers killed at Deser One, but was unsuccessful in negotiating the release of the Embassy hostages. In 2010 he was a passenger on the Mavi Marmara protest ship headed for Gaza when it was seized by Israel; he was held brieffly by Israel and then expelled.

Labels:

Israel,

Middle Eastern Christians,

obituaries,

Palestine

Tuesday, January 3, 2017

January 4, 1917: Russian Battleship Peresvet is Sunk Off Port Said

|

| Imperial Russian Navy Bttleship Persevet in 1901 |

My post today is not as important as any of those things. Only four days into the New Year, the Imperial Russian Navy Battleship Peresvet (also transliterated Peresvyet, Peresv'et: Пересвет) was sunk by a mine several miles off Egypt's Port Said.

Now, several Russian warships were in the Mediterranean when the Turks closed the Straits late in 1914, and they joined with the British and French Mediterranean Squadrons, but Peresvet was not one of them. In fact, what it was doing off Port Said is a rather bizarre tale in its own right. She was headed to the Russian White Sea Fleet in the far north, from Asian waters.

|

| Sagami (rear) in Japanese service |

In World War I, Japan and Russia suddenly found themselves on the same side in the war, and in 1916, Japan sold her (back) to Russia. In April 1916, in Vladivostok, she resumed her previous name and was reclassified as an armored cruiser. She then ran aground and had to be refloated. She was assigned to Russia's White Sea Fleet, She reached Port Said, and put in for repairs. Ten nautical miles off Port Said on January 4, 1917, she hit two mines and sank, with total losses somewhere between 116 and 167. The mines had been laid by the German submarine U-73.

Labels:

1948 War,

Egypt,

First World War,

Germany,

Russia

Monday, January 2, 2017

Rerun for Eastern Christmas: The Coptic Legends of the Holy Family on the Flight into Egypt

Those Eastern Christians who follow the Julian Calendar will celebrate Christmas this Saturday, January 7.

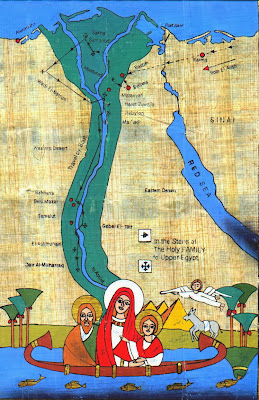

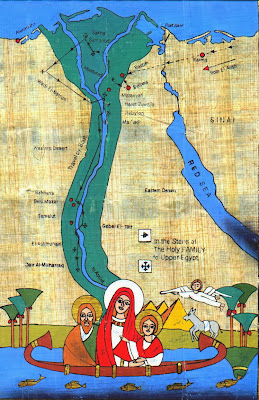

Since 2009, I have annually noted the rich Coptic traditions of the Holy Family's flight into Egypt, which expands the couple of verses in the Gospel of Matthew, by offering a detailed story of a three-year sojourn and visits up and down the Nile. More recently I've added a map and some pictures, and fixed a few errors. As always, despite the obvious apocryphal nature of these tales, I intend to respect the charm of the stories while noting some of the improbabilities. My revised and illustrated version:

Since we're in between Western Christmas and Eastern Christmas, I thought it might be a useful time to call to your attention the extremely detailed traditions Egypt's Copts maintain about the Holy Family and the Flight into Egypt. There is hardly a Christian church in Egypt — and there are some mosques, too, since Jesus and Mary are highly venerated in Islam — that doesn't claim that Jesus, Mary and Joseph dropped by for a while. They must have been constantly on the move to have covered so much ground, but you can't build up a good pilgrimage trade if you don't stop frequently.

Now, the Flight into Egypt gets only a couple of verses in the Bible and is only mentioned in one Gospel, Matthew, (Matthew 2, 13-14 and 19) so the extremely detailed accounts of the Coptic stories have more to do with pious elaboration — or pilgrimage tourism — than history, but the stories can be quite charming. Some are based on an apocryphal Armenian infancy gospel, some on local traditions, etc. The Coptic traditions hold that the Holy Family spent three years in Egypt.

I am shamelessly cribbing this from Chapter XXXI of the late Otto Meinardus' Christian Egypt Ancient and Modern, (Cairo: AUC Press, 1965; Revised Edition 1977). Meinardus was a major figure in Coptic studies; German-born, he wrote mostly in English or French, taught at the American University in Cairo, and was an ordained Lutheran pastor. (Judge for yourself what Martin Luther would have thought of some of these stories.) He died in 2005. But I have to condense all the details considerably; his chapter runs over 40 pages. There's also a detailed online site, with pictures (text approved personally by Coptic Pope Shenouda, they say), for those interested. And tours are available;this site also offers a travelogue.

It

seems the Holy Family traveled with a midwife named Salome who isn't

mentioned in the Gospel but plays a role in the Coptic stories. Instead

of heading straight to Egypt to escape the wrath of Herod, they seem to

have zigzagged to the Plain of Jericho, then Ashkelon, then Hebron (at

least according to the various churches and monasteries situated in

those places), then proceeded to enter Egypt via the Land of Goshen, en

route to the town of Bilbays. Along the way they had an encounter with a

dragon in a cave, and were approached by wild lions, but of course

they all bowed down to the Baby Jesus. At Bilbays they rested under a

large tree, which was venerated in the Middle Ages by both Muslims and

Christians as the Virgin's Tree, which stood until 1850. Then they

headed to Samannud, where there is a church on the site of a well

blessed by Jesus. (Early Christian apocryphal infancy Gospels, as well

as the Qur'an, have Jesus talking while still in the cradle.) Then they

detoured northward to the Mediterranean coast at Burollos, stopping

there according to the monks of the place. Then, perhaps at Basus or

Sakha in Gharbiyya (Meinardus speculates on the place), Jesus left his

footprint on a stone.

It

seems the Holy Family traveled with a midwife named Salome who isn't

mentioned in the Gospel but plays a role in the Coptic stories. Instead

of heading straight to Egypt to escape the wrath of Herod, they seem to

have zigzagged to the Plain of Jericho, then Ashkelon, then Hebron (at

least according to the various churches and monasteries situated in

those places), then proceeded to enter Egypt via the Land of Goshen, en

route to the town of Bilbays. Along the way they had an encounter with a

dragon in a cave, and were approached by wild lions, but of course

they all bowed down to the Baby Jesus. At Bilbays they rested under a

large tree, which was venerated in the Middle Ages by both Muslims and

Christians as the Virgin's Tree, which stood until 1850. Then they

headed to Samannud, where there is a church on the site of a well

blessed by Jesus. (Early Christian apocryphal infancy Gospels, as well

as the Qur'an, have Jesus talking while still in the cradle.) Then they

detoured northward to the Mediterranean coast at Burollos, stopping

there according to the monks of the place. Then, perhaps at Basus or

Sakha in Gharbiyya (Meinardus speculates on the place), Jesus left his

footprint on a stone.

Needless to say, they could not ignore the Wadi Natrun, the Coptic version of Mount Athos, where the four great monasteries of the Desert Fathers still stand (but of course didn't then as Christianity hadn't been founded yet), though why they were wandering in the desert instead of the delta in those days isn't explained. Passing by from a distance, Jesus said to his mother, "Know O my Mother, that in this desert there shall live many monks, ascetes and spiritual fighters, and they shall serve God like angels." (Apparently Mary would have known what a "monk" was, though it's hard to know why.) Anyway, you can ask the monks if you doubt any of this.

Even though Cairo wasn't there yet, you know Cairo isn't going to let all these other towns have a claim and not find some of its own, don't you? First they went to On, the ancient Heliopolis, not on the site of the modern suburb of that name but on the site of Matariyya. There Jesus took Joseph's staff, dug a well, and planted the staff, which grew into a tree which became a goal of pilgrimage and was venerated by Muslims as well as Christians. (The Qur'an has a story of Mary resting under a palm tree, and this and the Matariyya tree became conflated in later folklore. The Matariyya tree is a sycamore.) The present tree, still venerated, is alleged to be grown from the shoot of an older tree:

From there, the Holy Family went to a site

where, centuries later, the Harat Zuwaila quarter of Cairo would rise;

the Church of the Virgin there is one of the oldest in Cairo proper, and

the convent has a well blessed by Jesus.

(If you're wondering why I haven't mentioned their stop in the Fortress of Babylon, in a church many tourists visit today, it's because they stopped there only after their tour of Upper Egypt. Trust me, it's coming.)

Next they went to Ma‘adi, today an elite southern suburb of Cairo, and attended a synagogue. Joseph got to know some Nile boatmen, who offered to take them to Upper Egypt. (You're wondering how an exiled carpenter and family fleeing from King Herod can afford all this Grand Tour? Don't be so cynical: the legend has it covered: using the gold, frankincense and myrrh brought by the Magi.)

I'm going to condense a bit here since every Church of St. Mary up the Nile seems to mark a site where the boat stopped and they visited a well or a palm tree. But since Upper Egypt remains one of the more Christian parts of the country, they couldn't skip such Christian centers as Sammalout, Asyut, al-‘Ashnmunein, or the great monastery known as Deir al-Muharraq.

One of the legendary sub-stories here deserves telling, though. Up near al-‘Ashmunein, two brigands who had been pursuing the Holy Family since Matariyya (must be the gold, frankincense and myrrh again) tried to rob them. They grabbed Jesus and Mary cried, and one of the robbers repented, and they left them. And — as any folklorist should have figured out by now — these were the same two thieves, including the same Good Thief, who would be crucified alongside Jesus! How could it be otherwise?

The

constant travels were finally relieved when the Holy Family were taken

in by a devout Jew and lived for six months (and ten days: I told you

the stories are detailed) at the site of the Monastery of Deir

al-Muharraq, south

of al-Qusiya. The monks of the monastery say it was the first monastery

in Egypt, built just after the arrival of Saint Mark as the Apostle of

Egypt. If you doubt that, take it up with the monks, not me. Or with

the monks at St. Anthony's in the Eastern Desert, which is usually seen

as the earliest.)

Then

the angel came to Joseph and told him it was safe to go back to

Palestine. (That part actually is in the Gospel of Matthew, unlike

everything else in this post.) They stopped at pretty much every Coptic

village that would ever have a Church of the Virgin on their way back

down the Nile, and feeling they had not yet done enough for future

Cairo tourism, they stopped inside the Roman fortress known as Babylon

and, perhaps having run out of gold and frankincense, stayed in a cave

that is today the crypt of the church of Saint Sergius (Abu Sarga),

conveniently adjacent to the Coptic Museum and included on many Cairo

tours.

I hope I don't sound too cynical here: the stories are charming and are clearly a pious attempt to elaborate on a brief reference in the Gospel in order to make the Christian link to Egypt more tangible to believers. On the other hand, the sense that every Church of Saint Mary in Egypt actually sheltered the Virgin and Child seems a bit credulous.

I hope my Coptic friends recognize that I am helping spread knowledge of your tradition, even if I may not accept every detail as historically attested. I'd really like to know more about that dragon.

Since 2009, I have annually noted the rich Coptic traditions of the Holy Family's flight into Egypt, which expands the couple of verses in the Gospel of Matthew, by offering a detailed story of a three-year sojourn and visits up and down the Nile. More recently I've added a map and some pictures, and fixed a few errors. As always, despite the obvious apocryphal nature of these tales, I intend to respect the charm of the stories while noting some of the improbabilities. My revised and illustrated version:

Since we're in between Western Christmas and Eastern Christmas, I thought it might be a useful time to call to your attention the extremely detailed traditions Egypt's Copts maintain about the Holy Family and the Flight into Egypt. There is hardly a Christian church in Egypt — and there are some mosques, too, since Jesus and Mary are highly venerated in Islam — that doesn't claim that Jesus, Mary and Joseph dropped by for a while. They must have been constantly on the move to have covered so much ground, but you can't build up a good pilgrimage trade if you don't stop frequently.

Now, the Flight into Egypt gets only a couple of verses in the Bible and is only mentioned in one Gospel, Matthew, (Matthew 2, 13-14 and 19) so the extremely detailed accounts of the Coptic stories have more to do with pious elaboration — or pilgrimage tourism — than history, but the stories can be quite charming. Some are based on an apocryphal Armenian infancy gospel, some on local traditions, etc. The Coptic traditions hold that the Holy Family spent three years in Egypt.

I am shamelessly cribbing this from Chapter XXXI of the late Otto Meinardus' Christian Egypt Ancient and Modern, (Cairo: AUC Press, 1965; Revised Edition 1977). Meinardus was a major figure in Coptic studies; German-born, he wrote mostly in English or French, taught at the American University in Cairo, and was an ordained Lutheran pastor. (Judge for yourself what Martin Luther would have thought of some of these stories.) He died in 2005. But I have to condense all the details considerably; his chapter runs over 40 pages. There's also a detailed online site, with pictures (text approved personally by Coptic Pope Shenouda, they say), for those interested. And tours are available;this site also offers a travelogue.

It

seems the Holy Family traveled with a midwife named Salome who isn't

mentioned in the Gospel but plays a role in the Coptic stories. Instead

of heading straight to Egypt to escape the wrath of Herod, they seem to

have zigzagged to the Plain of Jericho, then Ashkelon, then Hebron (at

least according to the various churches and monasteries situated in

those places), then proceeded to enter Egypt via the Land of Goshen, en

route to the town of Bilbays. Along the way they had an encounter with a

dragon in a cave, and were approached by wild lions, but of course

they all bowed down to the Baby Jesus. At Bilbays they rested under a

large tree, which was venerated in the Middle Ages by both Muslims and

Christians as the Virgin's Tree, which stood until 1850. Then they

headed to Samannud, where there is a church on the site of a well

blessed by Jesus. (Early Christian apocryphal infancy Gospels, as well

as the Qur'an, have Jesus talking while still in the cradle.) Then they

detoured northward to the Mediterranean coast at Burollos, stopping

there according to the monks of the place. Then, perhaps at Basus or

Sakha in Gharbiyya (Meinardus speculates on the place), Jesus left his

footprint on a stone.

It

seems the Holy Family traveled with a midwife named Salome who isn't

mentioned in the Gospel but plays a role in the Coptic stories. Instead

of heading straight to Egypt to escape the wrath of Herod, they seem to

have zigzagged to the Plain of Jericho, then Ashkelon, then Hebron (at

least according to the various churches and monasteries situated in

those places), then proceeded to enter Egypt via the Land of Goshen, en

route to the town of Bilbays. Along the way they had an encounter with a

dragon in a cave, and were approached by wild lions, but of course

they all bowed down to the Baby Jesus. At Bilbays they rested under a

large tree, which was venerated in the Middle Ages by both Muslims and

Christians as the Virgin's Tree, which stood until 1850. Then they

headed to Samannud, where there is a church on the site of a well

blessed by Jesus. (Early Christian apocryphal infancy Gospels, as well

as the Qur'an, have Jesus talking while still in the cradle.) Then they

detoured northward to the Mediterranean coast at Burollos, stopping

there according to the monks of the place. Then, perhaps at Basus or

Sakha in Gharbiyya (Meinardus speculates on the place), Jesus left his

footprint on a stone.Needless to say, they could not ignore the Wadi Natrun, the Coptic version of Mount Athos, where the four great monasteries of the Desert Fathers still stand (but of course didn't then as Christianity hadn't been founded yet), though why they were wandering in the desert instead of the delta in those days isn't explained. Passing by from a distance, Jesus said to his mother, "Know O my Mother, that in this desert there shall live many monks, ascetes and spiritual fighters, and they shall serve God like angels." (Apparently Mary would have known what a "monk" was, though it's hard to know why.) Anyway, you can ask the monks if you doubt any of this.

Even though Cairo wasn't there yet, you know Cairo isn't going to let all these other towns have a claim and not find some of its own, don't you? First they went to On, the ancient Heliopolis, not on the site of the modern suburb of that name but on the site of Matariyya. There Jesus took Joseph's staff, dug a well, and planted the staff, which grew into a tree which became a goal of pilgrimage and was venerated by Muslims as well as Christians. (The Qur'an has a story of Mary resting under a palm tree, and this and the Matariyya tree became conflated in later folklore. The Matariyya tree is a sycamore.) The present tree, still venerated, is alleged to be grown from the shoot of an older tree:

|

| The Virgin's Tree, Matariyya |

|

| Harat Zuwaila Church of the Virgin |

(If you're wondering why I haven't mentioned their stop in the Fortress of Babylon, in a church many tourists visit today, it's because they stopped there only after their tour of Upper Egypt. Trust me, it's coming.)

Next they went to Ma‘adi, today an elite southern suburb of Cairo, and attended a synagogue. Joseph got to know some Nile boatmen, who offered to take them to Upper Egypt. (You're wondering how an exiled carpenter and family fleeing from King Herod can afford all this Grand Tour? Don't be so cynical: the legend has it covered: using the gold, frankincense and myrrh brought by the Magi.)

I'm going to condense a bit here since every Church of St. Mary up the Nile seems to mark a site where the boat stopped and they visited a well or a palm tree. But since Upper Egypt remains one of the more Christian parts of the country, they couldn't skip such Christian centers as Sammalout, Asyut, al-‘Ashnmunein, or the great monastery known as Deir al-Muharraq.

One of the legendary sub-stories here deserves telling, though. Up near al-‘Ashmunein, two brigands who had been pursuing the Holy Family since Matariyya (must be the gold, frankincense and myrrh again) tried to rob them. They grabbed Jesus and Mary cried, and one of the robbers repented, and they left them. And — as any folklorist should have figured out by now — these were the same two thieves, including the same Good Thief, who would be crucified alongside Jesus! How could it be otherwise?

|

| Deir al-Muharraq Today |

|

| Abu Sarga Church Crypt |

I hope I don't sound too cynical here: the stories are charming and are clearly a pious attempt to elaborate on a brief reference in the Gospel in order to make the Christian link to Egypt more tangible to believers. On the other hand, the sense that every Church of Saint Mary in Egypt actually sheltered the Virgin and Child seems a bit credulous.

I hope my Coptic friends recognize that I am helping spread knowledge of your tradition, even if I may not accept every detail as historically attested. I'd really like to know more about that dragon.

Labels:

Christmas,

Copts,

Egypt,

Middle Eastern Christians

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)