It's still several hours from 2015 here in the US, but the New Year has already arrived in Dubai. Having last year claimed to have set the world record for New Year's fireworks displays. How to follow up this year? Try to outdo last year, of course. I mean if you've got the world's tallest building, you might as well appear to blow it up once a year.

Wednesday, December 31, 2014

Tuesday, December 30, 2014

"Such a Band of Wild Men": the British Military Intelligence Section in Cairo, December 1914, Part I

The British military General Headquarters in Cairo War Diary for December 22, 1914 (100 years ago last week) reportedly notes "Organisation Military Intelligence Department proceeding under Captain Newcombe R.E. [Royal Engineers] with five other officers sent from home. Badly needed."

Though the text seems to imply six, most sources indicate that five men constituted the officers of the new Military Intelligence unit in Cairo in mid-December, though that number would grow. Most arrived in Egypt between about December 11 and 22. The five were not exactly never to be heard from again: they included then-Captain Stewart F. Newcombe, 36, a military engineer and veteran of the Boer War who would go on to play a prominent role in the Arab Revolt, at Gallipoli, and elsewhere in the war; Leonard Woolley, 34, Oxford archaeologist and excavator of Carchemish (better known for his postwar excavations at Ur); Aubrey Herbert, 34, Member of Parliament and younger son of the Earl of Carnarvon (and half-brother of the next Lord Carnarvon, who would fund the discoverer of Tutankhamun's tomb); Herbert, who would twice be offered the throne of Albania, is said to be the model for Sandy Arbuthnot in John Buchan's novel Greenmantle; George A. Lloyd, 35, another Member of Parliament and heir to business wealth who would eventually, as Lord Lloyd, be the High Commissioner in Egypt in the mid-1920s and write the two-volume history Egypt Since Cromer; and finally, the only one of the group under 30, a diminutive recently commissioned second lieutenant and budding 26-year-old archaeologist named Thomas Edward Lawrence. Usually better known these days as Lawrence of Arabia. In Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence would refer to the group as "such a band of wild men as we were."

Several of these men would later form part of the well-known Arab Bureau, along with others such as D.G. Hogarth, Herbert Garland, and Gertrude Bell. But the Arab Bureau would not be formed until December of 1915, when Sir Mark Sykes set it up to increase the role of Cairo at the expense of the India Office in the Middle East.

Of the five new arrivals, only Newcombe was a professional military man, though all had some experience in intelligence work; Woolley and Lawrence and Newcombe had worked together before the war. I'll have more on these men in Part III.

|

| Gilbert Clayton |

|

| The old Savoy Hotel |

|

| The Grand Continetal in better days |

Ah, but some of you are saying, that doesn't look anything like British Military HQ in David Lean's 1962 epic film, Lawrence of Arabia. (The only clip I could find on YouTube is actually dubbed in Spanish, which may give you a clue):

That's not Cairo. It's the Plaza de España complex in Seville, Spain. Grandiiose, majestic, and not what it looked like.

In Part II, I'll discuss the chain of command of the Intelligence section.

|

| Location of the old Savoy Hotel |

Labels:

Egypt,

intelligence,

The UK

Thursday, December 25, 2014

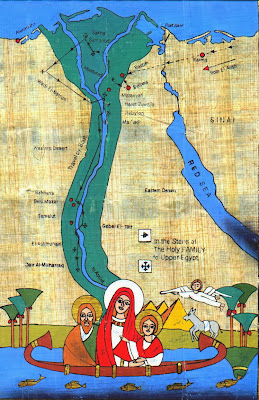

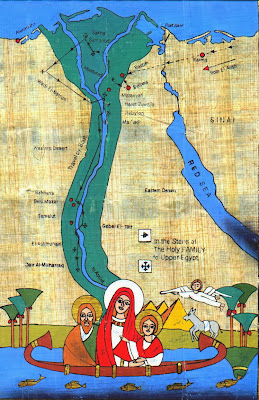

My Christmas Rerun: The Coptic Folklore Stories Surrounding the Flight Into Egypt

A Merry Christmas to readers who celebrate it today, though the majority of Middle Eastern Christians celebrate in January. This year's rerun of my post on the Coptic folklore traditions of the itinerary of the Holy Family during the Flight Into Egypt comes at a time when the Egyptian government is trying to promote the idea of Christian pilgrimage as a way to bolster tourism, and Coptic Pope Tawadros II helped launch the program with the line, "Jesus was the first tourist to Egypt." [Herodotus might disagree.]

Since 2009, I have annually noted the rich Coptic traditions of the Holy Family's flight into Egypt, which expands the couple of verses in the Gospel of Matthew, by offering a detailed story of a three-year sojourn and visits up and down the Nile. More recently I've added a map and some pictures, and fixed a few errors. As always, despite the obvious apocryphal nature of these tales, I intend to respect the charm of the stories while noting some of the improbabilities. My revised and illustrated version:

Since we're in between Western Christmas and Eastern Christmas, I thought it might be a useful time to call to your attention the extremely detailed traditions Egypt's Copts maintain about the Holy Family and the Flight into Egypt. There is hardly a Christian church in Egypt — and there are some mosques, too, since Jesus and Mary are highly venerated in Islam — that doesn't claim that Jesus, Mary and Joseph dropped by for a while. They must have been constantly on the move to have covered so much ground, but you can't build up a good pilgrimage trade if you don't stop frequently.

Now, the Flight into Egypt gets only a couple of verses in the Bible and is only mentioned in one Gospel, Matthew, (Matthew 2, 13-14 and 19) so the extremely detailed accounts of the Coptic stories have more to do with pious elaboration — or pilgrimage tourism — than history, but the stories can be quite charming. Some are based on an apocryphal Armenian infancy gospel, some on local traditions, etc. The Coptic traditions hold that the Holy Family spent three years in Egypt.

I am shamelessly cribbing this from Chapter XXXI of the late Otto Meinardus' Christian Egypt Ancient and Modern, (Cairo: AUC Press, 1965; Revised Edition 1977). Meinardus was a major figure in Coptic studies; German-born, he wrote mostly in English or French, taught at the American University in Cairo, and was an ordained Lutheran pastor. (Judge for yourself what Martin Luther would have thought of some of these stories.) He died in 2005. But I have to condense all the details considerably; his chapter runs over 40 pages. There's also a detailed online site, with pictures (text approved personally by Coptic Pope Shenouda, they say), for those interested. And tours are available;this site also offers a travelogue.

It

seems the Holy Family traveled with a midwife named Salome who isn't

mentioned in the Gospel but plays a role in the Coptic stories. Instead

of heading straight to Egypt to escape the wrath of Herod, they seem to

have zigzagged to the Plain of Jericho, then Ashkelon, then Hebron (at

least according to the various churches and monasteries situated in

those places), then proceeded to enter Egypt via the Land of Goshen, en

route to the town of Bilbays. Along the way they had an encounter with a

dragon in a cave, and were approached by wild lions, but of course

they all bowed down to the Baby Jesus. At Bilbays they rested under a

large tree, which was venerated in the Middle Ages by both Muslims and

Christians as the Virgin's Tree, which stood until 1850. Then they

headed to Samannud, where there is a church on the site of a well

blessed by Jesus. (Early Christian apocryphal infancy Gospels, as well

as the Qur'an, have Jesus talking while still in the cradle.) Then they

detoured northward to the Mediterranean coast at Burollos, stopping

there according to the monks of the place. Then, perhaps at Basus or

Sakha in Gharbiyya (Meinardus speculates on the place), Jesus left his

footprint on a stone.

It

seems the Holy Family traveled with a midwife named Salome who isn't

mentioned in the Gospel but plays a role in the Coptic stories. Instead

of heading straight to Egypt to escape the wrath of Herod, they seem to

have zigzagged to the Plain of Jericho, then Ashkelon, then Hebron (at

least according to the various churches and monasteries situated in

those places), then proceeded to enter Egypt via the Land of Goshen, en

route to the town of Bilbays. Along the way they had an encounter with a

dragon in a cave, and were approached by wild lions, but of course

they all bowed down to the Baby Jesus. At Bilbays they rested under a

large tree, which was venerated in the Middle Ages by both Muslims and

Christians as the Virgin's Tree, which stood until 1850. Then they

headed to Samannud, where there is a church on the site of a well

blessed by Jesus. (Early Christian apocryphal infancy Gospels, as well

as the Qur'an, have Jesus talking while still in the cradle.) Then they

detoured northward to the Mediterranean coast at Burollos, stopping

there according to the monks of the place. Then, perhaps at Basus or

Sakha in Gharbiyya (Meinardus speculates on the place), Jesus left his

footprint on a stone.

Needless to say, they could not ignore the Wadi Natrun, the Coptic version of Mount Athos, where the four great monasteries of the Desert Fathers still stand (but of course didn't then as Christianity hadn't been founded yet), though why they were wandering in the desert instead of the delta in those days isn't explained. Passing by from a distance, Jesus said to his mother, "Know O my Mother, that in this desert there shall live many monks, ascetes and spiritual fighters, and they shall serve God like angels." (Apparently Mary would have known what a "monk" was, though it's hard to know why.) Anyway, you can ask the monks if you doubt any of this.

Even though Cairo wasn't there yet, you know Cairo isn't going to let all these other towns have a claim and not find some of its own, don't you? First they went to On, the ancient Heliopolis, not on the site of the modern suburb of that name but on the site of Matariyya. There Jesus took Joseph's staff, dug a well, and planted the staff, which grew into a tree which became a goal of pilgrimage and was venerated by Muslims as well as Christians. (The Qur'an has a story of Mary resting under a palm tree, and this and the Matariyya tree became conflated in later folklore. The Matariyya tree is a sycamore.) The present tree, still venerated, is alleged to be grown from the shoot of an older tree:

From there, the Holy Family went to a site

where, centuries later, the Harat Zuwaila quarter of Cairo would rise;

the Church of the Virgin there is one of the oldest in Cairo proper, and

the convent has a well blessed by Jesus.

(If you're wondering why I haven't mentioned their stop in the Fortress of Babylon, in a church many tourists visit today, it's because they stopped there only after their tour of Upper Egypt. Trust me, it's coming.)

Next they went to Ma‘adi, today an elite southern suburb of Cairo, and attended a synagogue. Joseph got to know some Nile boatmen, who offered to take them to Upper Egypt. (You're wondering how an exiled carpenter and family fleeing from King Herod can afford all this Grand Tour? Don't be so cynical: the legend has it covered: using the gold, frankincense and myrrh brought by the Magi.)

I'm going to condense a bit here since every Church of St. Mary up the Nile seems to mark a site where the boat stopped and they visited a well or a palm tree. But since Upper Egypt remains one of the more Christian parts of the country, they couldn't skip such Christian centers as Sammalout, Asyut, al-‘Ashnmunein, or the great monastery known as Deir al-Muharraq.

One of the legendary sub-stories here deserves telling, though. Up near al-‘Ashmunein, two brigands who had been pursuing the Holy Family since Matariyya (must be the gold, frankincense and myrrh again) tried to rob them. They grabbed Jesus and Mary cried, and one of the robbers repented, and they left them. And — as any folklorist should have figured out by now — these were the same two thieves, including the same Good Thief, who would be crucified alongside Jesus! How could it be otherwise?

The

constant travels were finally relieved when the Holy Family were taken

in by a devout Jew and lived for six months (and ten days: I told you

the stories are detailed) at the site of the Monastery of Deir

al-Muharraq, south

of al-Qusiya. The monks of the monastery say it was the first monastery

in Egypt, built just after the arrival of Saint Mark as the Apostle of

Egypt. If you doubt that, take it up with the monks, not me. Or with

the monks at St. Anthony's in the Eastern Desert, which is usually seen

as the earliest.)

Then

the angel came to Joseph and told him it was safe to go back to

Palestine. (That part actually is in the Gospel of Matthew, unlike

everything else in this post.) They stopped at pretty much every Coptic

village that would ever have a Church of the Virgin on their way back

down the Nile, and feeling they had not yet done enough for future

Cairo tourism, they stopped inside the Roman fortress known as Babylon

and, perhaps having run out of gold and frankincense, stayed in a cave

that is today the crypt of the church of Saint Sergius (Abu Sarga),

conveniently adjacent to the Coptic Museum and included on many Cairo

tours.

I hope I don't sound too cynical here: the stories are charming and are clearly a pious attempt to elaborate on a brief reference in the Gospel in order to make the Christian link to Egypt more tangible to believers. On the other hand, the sense that every Church of Saint Mary in Egypt actually sheltered the Virgin and Child seems a bit credulous.

I hope my Coptic friends recognize that I am helping spread knowledge of your tradition, even if I may not accept every detail as historically attested. I'd really like to know more about that dragon.

Since 2009, I have annually noted the rich Coptic traditions of the Holy Family's flight into Egypt, which expands the couple of verses in the Gospel of Matthew, by offering a detailed story of a three-year sojourn and visits up and down the Nile. More recently I've added a map and some pictures, and fixed a few errors. As always, despite the obvious apocryphal nature of these tales, I intend to respect the charm of the stories while noting some of the improbabilities. My revised and illustrated version:

Since we're in between Western Christmas and Eastern Christmas, I thought it might be a useful time to call to your attention the extremely detailed traditions Egypt's Copts maintain about the Holy Family and the Flight into Egypt. There is hardly a Christian church in Egypt — and there are some mosques, too, since Jesus and Mary are highly venerated in Islam — that doesn't claim that Jesus, Mary and Joseph dropped by for a while. They must have been constantly on the move to have covered so much ground, but you can't build up a good pilgrimage trade if you don't stop frequently.

Now, the Flight into Egypt gets only a couple of verses in the Bible and is only mentioned in one Gospel, Matthew, (Matthew 2, 13-14 and 19) so the extremely detailed accounts of the Coptic stories have more to do with pious elaboration — or pilgrimage tourism — than history, but the stories can be quite charming. Some are based on an apocryphal Armenian infancy gospel, some on local traditions, etc. The Coptic traditions hold that the Holy Family spent three years in Egypt.

I am shamelessly cribbing this from Chapter XXXI of the late Otto Meinardus' Christian Egypt Ancient and Modern, (Cairo: AUC Press, 1965; Revised Edition 1977). Meinardus was a major figure in Coptic studies; German-born, he wrote mostly in English or French, taught at the American University in Cairo, and was an ordained Lutheran pastor. (Judge for yourself what Martin Luther would have thought of some of these stories.) He died in 2005. But I have to condense all the details considerably; his chapter runs over 40 pages. There's also a detailed online site, with pictures (text approved personally by Coptic Pope Shenouda, they say), for those interested. And tours are available;this site also offers a travelogue.

It

seems the Holy Family traveled with a midwife named Salome who isn't

mentioned in the Gospel but plays a role in the Coptic stories. Instead

of heading straight to Egypt to escape the wrath of Herod, they seem to

have zigzagged to the Plain of Jericho, then Ashkelon, then Hebron (at

least according to the various churches and monasteries situated in

those places), then proceeded to enter Egypt via the Land of Goshen, en

route to the town of Bilbays. Along the way they had an encounter with a

dragon in a cave, and were approached by wild lions, but of course

they all bowed down to the Baby Jesus. At Bilbays they rested under a

large tree, which was venerated in the Middle Ages by both Muslims and

Christians as the Virgin's Tree, which stood until 1850. Then they

headed to Samannud, where there is a church on the site of a well

blessed by Jesus. (Early Christian apocryphal infancy Gospels, as well

as the Qur'an, have Jesus talking while still in the cradle.) Then they

detoured northward to the Mediterranean coast at Burollos, stopping

there according to the monks of the place. Then, perhaps at Basus or

Sakha in Gharbiyya (Meinardus speculates on the place), Jesus left his

footprint on a stone.

It

seems the Holy Family traveled with a midwife named Salome who isn't

mentioned in the Gospel but plays a role in the Coptic stories. Instead

of heading straight to Egypt to escape the wrath of Herod, they seem to

have zigzagged to the Plain of Jericho, then Ashkelon, then Hebron (at

least according to the various churches and monasteries situated in

those places), then proceeded to enter Egypt via the Land of Goshen, en

route to the town of Bilbays. Along the way they had an encounter with a

dragon in a cave, and were approached by wild lions, but of course

they all bowed down to the Baby Jesus. At Bilbays they rested under a

large tree, which was venerated in the Middle Ages by both Muslims and

Christians as the Virgin's Tree, which stood until 1850. Then they

headed to Samannud, where there is a church on the site of a well

blessed by Jesus. (Early Christian apocryphal infancy Gospels, as well

as the Qur'an, have Jesus talking while still in the cradle.) Then they

detoured northward to the Mediterranean coast at Burollos, stopping

there according to the monks of the place. Then, perhaps at Basus or

Sakha in Gharbiyya (Meinardus speculates on the place), Jesus left his

footprint on a stone.Needless to say, they could not ignore the Wadi Natrun, the Coptic version of Mount Athos, where the four great monasteries of the Desert Fathers still stand (but of course didn't then as Christianity hadn't been founded yet), though why they were wandering in the desert instead of the delta in those days isn't explained. Passing by from a distance, Jesus said to his mother, "Know O my Mother, that in this desert there shall live many monks, ascetes and spiritual fighters, and they shall serve God like angels." (Apparently Mary would have known what a "monk" was, though it's hard to know why.) Anyway, you can ask the monks if you doubt any of this.

Even though Cairo wasn't there yet, you know Cairo isn't going to let all these other towns have a claim and not find some of its own, don't you? First they went to On, the ancient Heliopolis, not on the site of the modern suburb of that name but on the site of Matariyya. There Jesus took Joseph's staff, dug a well, and planted the staff, which grew into a tree which became a goal of pilgrimage and was venerated by Muslims as well as Christians. (The Qur'an has a story of Mary resting under a palm tree, and this and the Matariyya tree became conflated in later folklore. The Matariyya tree is a sycamore.) The present tree, still venerated, is alleged to be grown from the shoot of an older tree:

|

| The Virgin's Tree, Matariyya |

|

| Harat Zuwaila Church of the Virgin |

(If you're wondering why I haven't mentioned their stop in the Fortress of Babylon, in a church many tourists visit today, it's because they stopped there only after their tour of Upper Egypt. Trust me, it's coming.)

Next they went to Ma‘adi, today an elite southern suburb of Cairo, and attended a synagogue. Joseph got to know some Nile boatmen, who offered to take them to Upper Egypt. (You're wondering how an exiled carpenter and family fleeing from King Herod can afford all this Grand Tour? Don't be so cynical: the legend has it covered: using the gold, frankincense and myrrh brought by the Magi.)

I'm going to condense a bit here since every Church of St. Mary up the Nile seems to mark a site where the boat stopped and they visited a well or a palm tree. But since Upper Egypt remains one of the more Christian parts of the country, they couldn't skip such Christian centers as Sammalout, Asyut, al-‘Ashnmunein, or the great monastery known as Deir al-Muharraq.

One of the legendary sub-stories here deserves telling, though. Up near al-‘Ashmunein, two brigands who had been pursuing the Holy Family since Matariyya (must be the gold, frankincense and myrrh again) tried to rob them. They grabbed Jesus and Mary cried, and one of the robbers repented, and they left them. And — as any folklorist should have figured out by now — these were the same two thieves, including the same Good Thief, who would be crucified alongside Jesus! How could it be otherwise?

|

| Deir al-Muharraq Today |

|

| Abu Sarga Church Crypt |

I hope I don't sound too cynical here: the stories are charming and are clearly a pious attempt to elaborate on a brief reference in the Gospel in order to make the Christian link to Egypt more tangible to believers. On the other hand, the sense that every Church of Saint Mary in Egypt actually sheltered the Virgin and Child seems a bit credulous.

I hope my Coptic friends recognize that I am helping spread knowledge of your tradition, even if I may not accept every detail as historically attested. I'd really like to know more about that dragon.

Labels:

Christmas,

Copts,

holidays,

Middle Eastern Christians

Tuesday, December 23, 2014

Fairuz 2; More Carols in Arabic

I know I've been posting Fairuz singing Western carols with Arabic lyrics; I'll post her and other artists singing traditional Eastern music as the Eastern date of Christmas approaches.

Angels we Have Heard on High:

Her version of "Joy to the World" is about Beirut;

God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen:

Angels we Have Heard on High:

Her version of "Joy to the World" is about Beirut;

God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen:

Monday, December 22, 2014

'Tis the Season for Fairuz Singing Christmas Carols in Arabic

As Western Christmas approaches I offer Fairuz singing Christmas carols in Arabic. (Fairuz recently turned 80, so the first clip is pretty old.)

Jingle Bells:

Silent Night:

Go Tell it on the Mountain:

More to come.

Jingle Bells:

Silent Night:

Go Tell it on the Mountain:

More to come.

Egypt: General Intelligence Chief Replaced

|

| Muhammad Farid al-Tuhami |

The official reason being given is that he was replaced for health reasons, and it is reported he recently had a hip replacement.

He has been replaced by his Deputy, Khalid Fawzy, on an Acting basis.

A Note on Holiday Blogging

The Middle East Institute offices are closed during the holidays. I will continue posting to the blog, including my usual posts about Christmas in the Middle East and my World War I series, as well as noting key developments, but at a reduced pace.

Labels:

About the Blog,

holidays

Friday, December 19, 2014

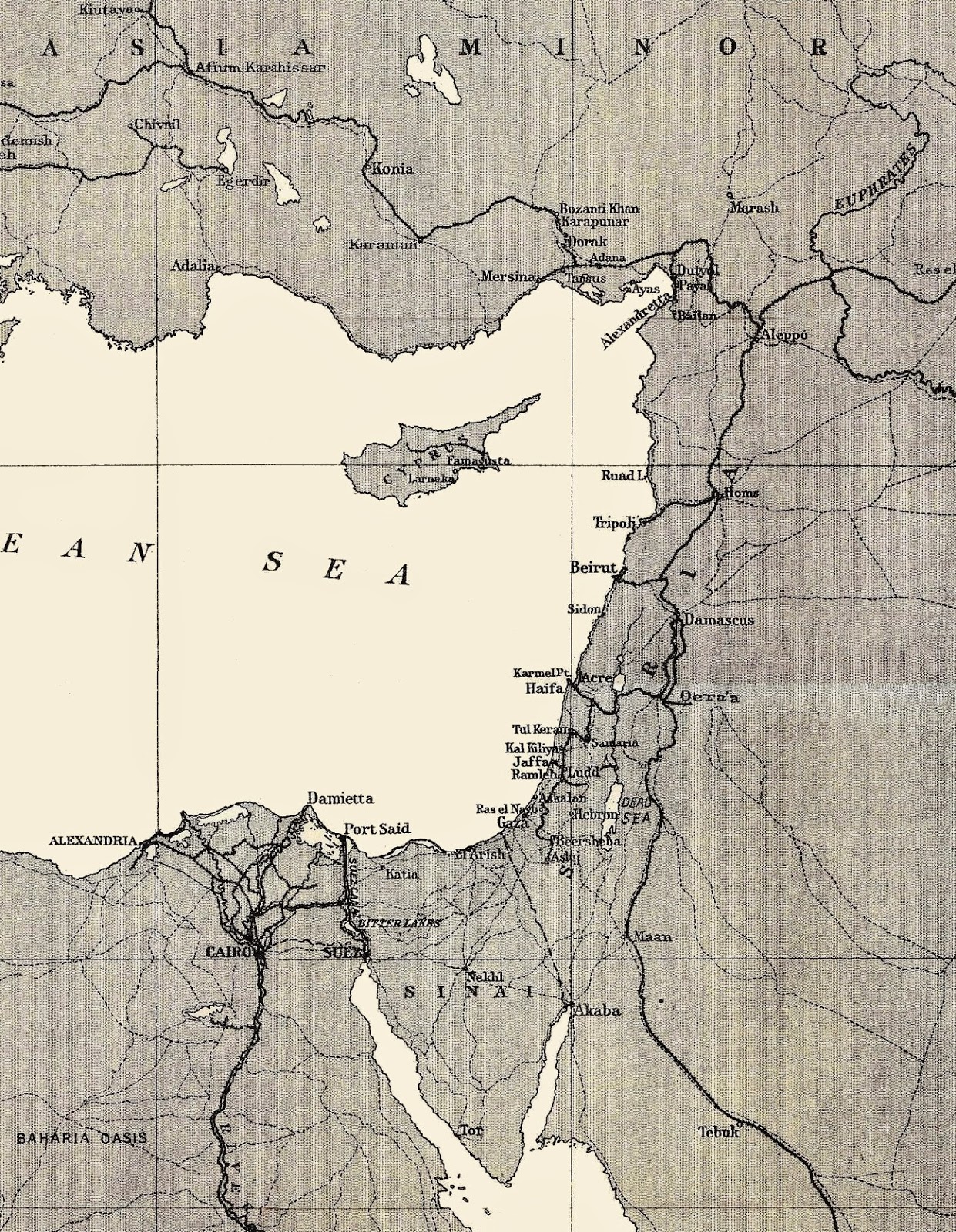

Britain Raids the Syrian Coast: HMS Doris at Alexandretta 1914

We have previously talked about the British proposal at the outset of the Great War in the Middle East for an amphibious landing at Alexandretta (İskenderun today); that post looked at the strategic importance of the port, and future posts will delve further with the fate of the landing project; but in the meantime, it's time to talk about Britain's naval operations on the Syrian coast a century ago.

Since the feared Turkish attack on the Suez Canal had not yet shown any sign of happening (it would come in late January), it was decided to use naval assets to reconnoiter and if possible raid the Syrian/Palestinian coast of the Ottoman Empire.

The ships would be HMS Doris, a British protected cruiser (a light cruiser with an armored deck), commanded by Captain Frank Larken, and the Russian protected cruiser Askold, Captain Sergey Ivanov. Askold had been serving in the Far East, but after the defeat of the German raider Emden was transferred to the Mediterranean. Since Turkey had closed the Straits, Askold could not reach Russian ports in the Black Sea, so she operated with British and French fleets.

Askold was unusual in the Russian fleet for its five funnels, which gave it an easily identifiable silhouette.

At the beginning of December 1914, Askold was sent to reconnoiter the coast and at Haifa cut out a German steamer (also named Haifa) and captured it.

She then proceeded to Port Said. There Vice Admiral Richard Peirse, Commander-in-Chief of Britain's East Indies (southeast Asia) station had recently arrived in Egypt to defend the Canal. On December 11, Peirse was instructed to dispatch Askold and Doris to the Syrian coast for reconnaissance and other operations. Askold left first, followed by Doris after an air reconnaissance confirmed that Turkish troops around Beersheba (Beersheva) had not left their camps to threaten the canal.

Askold proceeded to Beirut, where she sank two Turkish steamers; she landed landing parties for reconnaissance in several places.

HMS Doris, meanwhile, proceeded up the coast for what the British Official History calls "a series of remarkable adventures."

The Naval Review, Volume III, No. 4 (1915) contains a rather detailed account entitled "Three Months on the Syrian Coast," available free online from either Google Books or from The Naval Review website. The article, which has no byline but was clearly done by someone aboard the ship or with access to her logbooks, begins on page 621; I draw much of the rest of my narrative from it, as well as from the British official histories, ground forces and naval.

On December 13 Doris began her voyage up the coast, bombarding a Turkish fortification around al-‘Arish in Sinai. On the 15th she bombarded a Turkish position about two miles south of Ascalon and put a landing party ashore which occupied the position "and removed certain objects of military value or antiquarian interest." Turkish troops soon arrived but the landing party withdrew unscathed under the protection of Doris's guns.

Proceeding up the coast, Doris' seaplane carried out reconnaissance at Jaffa and again at Haifa. The Naval Review article tells a tale about the local official in Jaffa that reads a bit like wartime propaganda but deserves to be repeated anyway:

The airmen flew as far as Ramla but neither around Jaffa nor later around Haifa did they spot any Ottoman troop concentrations. Proceeding up the Lebanese coast another landing party went ashore near Sidon to cut the telegraph lines to Damascus:

At this point Captain Larken sent an ultimatum demanding the surrender of all railway engines and munitions of war or face bombardment; the local qaimaqam was given until 9 am the next day to reply. The Naval Review account continues:

Since the feared Turkish attack on the Suez Canal had not yet shown any sign of happening (it would come in late January), it was decided to use naval assets to reconnoiter and if possible raid the Syrian/Palestinian coast of the Ottoman Empire.

_IWM_Q_021174.jpg) |

| HMS Doris |

|

| Askold |

At the beginning of December 1914, Askold was sent to reconnoiter the coast and at Haifa cut out a German steamer (also named Haifa) and captured it.

|

| Admiral Richard Peirse |

Askold proceeded to Beirut, where she sank two Turkish steamers; she landed landing parties for reconnaissance in several places.

HMS Doris, meanwhile, proceeded up the coast for what the British Official History calls "a series of remarkable adventures."

The Naval Review, Volume III, No. 4 (1915) contains a rather detailed account entitled "Three Months on the Syrian Coast," available free online from either Google Books or from The Naval Review website. The article, which has no byline but was clearly done by someone aboard the ship or with access to her logbooks, begins on page 621; I draw much of the rest of my narrative from it, as well as from the British official histories, ground forces and naval.

|

| The Eastern Mediterranean in 1914 |

Proceeding up the coast, Doris' seaplane carried out reconnaissance at Jaffa and again at Haifa. The Naval Review article tells a tale about the local official in Jaffa that reads a bit like wartime propaganda but deserves to be repeated anyway:

While off Jaffa and Haifa, seaplane reconnaissances were carried out by Bimbashi Herbert, late of the Egyptian Survey, and Lieut. Destrem, of the French Flying Service. At the former place the arrival of the seaplane caused terror and affright; the Kaimakam, a notorious prosecutor of enemy non combatants, fled headlong from the Serail and concealed himself in a foreigner’s cellar. His Excellency emerged only when seaplane and ship were alike out of sight. He then blustered forth and sought to divert attention from his own unimpressive conduct by ordering the arrest of a number of old women, who, not having cellars in which to hide, had innocently put up umbrellas or parasols to fend off the anticipated shower of umbrellas or parasols to fend off the anticipated shower of bombs. These unfortunate ladies were soundly beaten by the unchivalrous Kaimakam for having “signalled” with these umbrellas to the seaplane.["Bimbashi Herbert," mentioned here, was the ship's intelligence officer; "Bimbashi" is the rank of major in the Egyptian service. This is apparently one J.R. Herbert, not the far better known intelligence operative Aubrey Herbert, who this same week was settling in at British HQ in Cairo with T.E. Lawrence and others of the intelligence section, which I'll be talking about soon.]

The airmen flew as far as Ramla but neither around Jaffa nor later around Haifa did they spot any Ottoman troop concentrations. Proceeding up the Lebanese coast another landing party went ashore near Sidon to cut the telegraph lines to Damascus:

On December 18th a party under Commander K. Brounger landed about 9 a.m. at a point about four miles south of Sidon. The coastal telegraph line (five wires) and the telephone to Damascus were carefully removed for a distance of nearly three quarters of a mile, the posts being cut down and in many cases sawn in three. As the road bridge within the area occupied had already been cut off from the road to the north by the action of the river, no time was wasted in its destruction. A number of the inhabitants stopped ploughing in order to converse with members of the party and a Turkish mounted gendarme rode up and down at furious speed some two miles away towards Sidon. There was no fighting, but an elderly Maronite, who had been to New York, was temporarily deprived of a fowling piece, which was likely to be highly dangerous to its possessor, and a number of tortoises and two rare frogs were brought off. The latter were subsequently presented by their captor, Bimbashi Herbert, to the Cairo Zoological Gardens.After the specimen collection, the Doris headed north to Alexandretta, where her target was the railroad. After dark on the 18th she sent a party ashore:

On arriving after nightfall off Alexandretta the Doris experienced one of the savage squalls which haunt that area, and for some time it was doubtful whether a boat could get away. At 11.15 p.m. however the weather moderated enough for Lieut. R. S. Hulme-Goodier, R.N.R. to land with a party at a point about two and a half miles along the coast northward from Jonah’s Pillar (Bab Yunus) and some eight miles in an airline from Alexandretta. Along this part of the coast the rail way runs only a few yards from high-water mark. A couple of rails were loosened and the telegraph wires were cut. The party, working in darkness and as silently as possible escaped observation from the Turkish patrols, but regained the ship with great difficulty owing to the heavy weather. Less than an hour after their return, a train was seen approaching at some eight miles an hour from the north, and many officers were specially called in order to see the expected fireworks, the ship being at the time less than 2,000 yards from the shore which is fairly steep-to all the way round that part of the gulf. Unfortunately the train was not loaded with ammunition. The engine jumped the damaged section and escaped into Alexandretta with terrified trumpetings. The train however was derailed, many of the trucks being telescoped and the contents, chiefly consisting of live camels, were spilt about.

At dawn another train was observed to be endeavouring to retire from the scene of the disaster and fire was opened on a railway bridge to the northward in order to cut off its retreat. The bridge, like so many on this branch of the Baghdad rail way, was built of steel girders and reinforced concrete, on which shell fire makes impression with difficulty. There was also a considerable sea running. The bridge was damaged, but not fatally, and fire was then directed upon the engine, which was wounded by two 12-pounder common in its Vitals. Proceeding southward, some of the trucks of the derailed train were observed to be on fire, and an immense tethered camel was seen apparently writhing in the flames. The sea had got up, and although every effort was made to put the poor beast out of its pain, it was unavailing until the creature ate the rope which tied it and so escaped.This was in the morning of December 19, 100 years ago today.

At this point Captain Larken sent an ultimatum demanding the surrender of all railway engines and munitions of war or face bombardment; the local qaimaqam was given until 9 am the next day to reply. The Naval Review account continues:

In the afternoon of the same day, an ultimatum was presented to the Kaimakam of Alexandretta, Fahtin Bey, in which 'the surrender, for purposes of immediate destruction, of all railway engines and munitions of war then in Alexandretta, was insisted upon under penalty of a bombardment of the railway and harbour works and the principal Government buildings. The ultimatum which could not have been drawn in a more stately manner had the surrender of the entire Ottoman Empire been demanded, was handed to His Excellency in person by Lieut. Pirie-Gordon, the Intelligence Officer, at 3 p.m. and he was informed that an answer would have to be forthcoming at 9 o'clock next morning.[This intelligence officer was apparently Harry Pirie-Gordon, who before the war had made a survey of the coast around Alexandretta and would later serve with the Arab Bureau.]

During the interval unceasing squalls flayed the bay, and although searchlights were played on the town, the rain was so heavy that little could be seen. It was afterwards learnt that the Turks had taken the opportunity to remove such stores as were still in the town under cover of the storm, but owing to the measures taken by the ship they were unable to smuggle out their engines. Next morning, with an eflrontery inspired by the best Prussian traditions, the Turkish Commander-in-Chief in Syria, Djemal Pasha, replied to the ultimatum threatening to massacre one or more British subjects from among the many civilians detained (contrary to international custom) by the Turks, for every Ottoman, combatant or non-combatant, killed in the bombardment, and utterly declining to surrender either engines or stores. Furthermore the United States Acting Consul, Mr. Bishop of the Standard Oil Company, (who very ably filled the difficult position of mediator throughout the whole of these negotiations) was allowed by the Turks to bring off telegrams from his Ambassador in Constantinople and from the British prisoners in Aleppo and Damascus requesting Captain Larken not to bombard Alexandretta. To this fantastic attempt at bluff the captain returned a short answer and informed Djemal Pasha that if he attempted to execute his infamous threat, he, his staff, and every one else who might have obeyed his orders to that end would be specially handed over by the terms of any Treaty of Peace to the British Government for trial and punishment both in person1 and property. A few hours’ grace was accorded for this threat to sink in, and the engines were demanded by 9 o’clock next morning.While awaiting that answer, Doris made a quiet sortie to the north to destroy a railway bridge.

During the interval the Doris headed north and landed a party under the Commander at the mouth of the Euzerli Chai near the town of Deurt Yol (four roads), which the Armenians call by its equivalent in their language, Chokmerjumen. The Turks opened fire at about 150-200 yards’ range from a trench in front of a small hut, after very kindly allowing the party to land unmolested. The slope of the beach here provided an excellent breastwork from behind which our people returned the Turks’ fire while the ship shelled them out of their trench. The party then advanced in open order to the railway bridge over the Euzerli Chai, over which it was carried by a two-span bridge of steel girders on reinforced concrete abutments. This was carefully blown up by Lieut. Edwards in such a way that one span was twisted and canted over at an angle of 15° as well as being shifted more than three feet out of the true, and the two northern piers were much damaged.

revealing the treasures within. An inspection of the telegraph reel showed that the stationmaster had been doing his duty up to the very moment of surrender, as an unfinished message to the nearest military post was found, in which the Doris was described as a destroyer. The telegraph instruments and the cash were seized in the King’s name by the Intelligence Oflicer, and Herbert removed certain notice boards as souvenirs. The three Armenians volubly insisted on being taken away as prisoners, explaining that the German railway authorities had made the Turks hang two stationmasters the previous day because the Doris had derailed a train, and they feared worse things if they were to be caught after their bridge had been blown up. They were taken on board where they provided exact and valuable information about the Turkish supplies and reinforcements which had passed through their station. Before retiring, a good many shots were fired into the station water tank, from which the water squirted in a most diverting manner through the bullet holes. Some telegraph poles were battered down. The casualties were Private A. H. Brimson, R.M.L.I. [Royal Marine Light Infantry], and one Turk wounded.After this side venture, Doris returned to the standoff at Alexandretta and the demand for the railway engines.

Next morning, December 22nd,. the Turks agreed to sacrifice their engines and produced two machines which the owners valued at £15,000. They were French built and are believed to have belonged to the old British company which had worked the Mersina-Adana railway before it was taken over by the Germans a few years ago. The Kaimakam, however, explained that he had no explosives and asked if some dynamite could be lent to him by the ship. Captain Larken very obligingly provided some gun-cotton, regretting that he had no dynamite to spare. Lieut. Edwards with a party of torpedo men, specially selected for the size of their beards (it being a Moslem town), was sent, with the Intelligence Oflicer and Staff-Paymaster F. J. K. Melsome as interpreters. The Turks stood on their dignity and declined to allow our people to have anything to do with the explosion. It was explained to the Kaimakam that if the gun-cotton were lent to the Turks without skilled supervision they might (a) hurt somebody by letting it off too soon, or (b) omit to use it for the purpose for which it had been ostensibly borrowed. The former danger was somewhat real, as the German railway engineer upon whom the Turks relied to blow up his own engines for them, declined with almost vulgar emphasis to do anything of the kind, whereat the Kaimakam blandly confessed that he had no one else who would dare, or even knew how, to do the job. Anxious however to oblige, when he found that his proposal to postpone the explosion until the German should be in a more tractable frame of mind was not entertained, he suggested that if the Doris’s torpedo-lieutenant were to lay the charges satisfactorily to himself, as representing His Britannic Majesty, he could then proceed to fire them, if lent for the purpose to the Ottoman Navy, in order that the actual explosion might be caused by an oflicer duly authorized to represent the Sultan. This proposal was readily accepted, and Mr. Bishop, the United States Acting Consul was witness that Lieut. Edwards, R.N., was rated as a Turkish Naval Officer for the rest of the day. Enjoying this dual capacity Lieut. Edwards afterwards superintended both sections of the explosions, although the actual firing, owing to the inaccessible position of the fuzes, was done by an agile Turkish quarryman under his immediate instruction. The rest of the day was deliberately wasted by the Turks, who exhausted every expedient in hopes of wearing out the patience of the British so as to induce them to agree to a postponement of the operation. Finally after an abrupt threat of bombardment within ten minutes, followed by the vigorous shaking of an unmannerly Ottoman officer of gendarmes, the harbourmaster, a prince of procrastinators, was cast into a shallow part of the sea. Almost immediately after this the matter was put through. The two engines, which had been running about, mournfully whistling from time to time, were caught by the exertions of a squad of cavalry which chased them in the dark. and held in the place of execution under the ship’s searchlights. They were then duly blown up.in the presence of Mr. Bishop, who attended Lieut. Edwards throughout to see fair play, as that officer was unable to speak Turkish and no other officer was allowed to approach the engines. The operation was one of some danger, as after the explosions, bits and bolts rained down over a con siderable area. When at last the party was able to put off, a final laugh was raised among its cold and hungry members when the harbourmaster, pathetically bootless, swordless, and wet, ambled up out of the darkness and remarked in a polite but melancholy voice, “I beseech you go away, the people are excited, oh please to go away, I implore, oh go away.” The party had been some eight hours on the beach on a bleak day, covered the whole time by the rifles of a considerable force of Turks who were posted behind walls and in houses commanding the various piers and cambers whereon the somewhat humorous events of the afternoon and evening were taking place.After the charade of a British naval lieutenant being officially a Turkish soldier for the purpose of destroying the engines had been duly witnessed by the neutral American Acting Consul (an oilman), the Doris left Alexandretta. Her adventures on the Syrian coast would continue, however, and I'll be providing Part Two soon.

Labels:

First World War,

Ottoman Empire,

Russia,

Syria,

The UK,

Turkey

Thursday, December 18, 2014

December 18, 1914: A Khedive becomes a Sultan, but Egypt Becomes a British Protectorate

In our discussion of the centennial of the First World War in the Middle East, we have already discussed the anomalous position of Egypt: though ruled by a hereditary Khedive, it was still de jure a province of the Ottoman Empire, paying annual tribute to Constantinople. But, since 1882, it had been de facto under British control, occupied by Britain, whose innocuously titled "British Agent and Consul-General" functioned as a virtual viceroy. It was an awkward legal status often referred to as "the veiled protectorate," and once Britain went to war with the Ottoman Empire, It became wholly untenable.

A century ago today, the veil came off. Britain declared a protectorate over Egypt, deposed the Khedive and installed his uncle as ruler with the new title of "Sultan," but it was not as simple as that, as there was a month or so of hard bargaining before the deed was done.

Lord Kitchener had been British Agent at the time of the outbreak of the war, when he was kept in Britain to take over the War Office. In his absence, Milne Cheetham was the Acting British Agent, with Ronald Storrs as his "Oriental Secretary," his Middle East expert.

Once Turkey entered the war, there was no question that Britain had to alter the status of Egypt. But to what? In London, many favored outright annexation, making Egypt as much a part of the Empire as India. The Agency in Cairo was alarmed: direct rule would alienate Egyptians and the Muslim world generally, while the policy since 1882 had been to govern through a local ruler. Cheetham and Storrs pleaded for a protectorate instead, On November 19, London agreed, but it took another month before the protectorate was proclaimed.

The reason was Britain needed a candidate for ruler of Egypt; the incumbent Khedive, ‘Abbas Hilmi II, was in Constantinople, recovering from a failed assassination attempt, and he was an inveterate opponent of British rule. Kitchener had been determined to depose him even before; now he had to go.

‘Abbas Hilmi II was the son of the Khedive Tawfiq and grandson of the great Isma‘il, the man who both glorified and bankrupted Egypt the previous century. Isma‘il had two surviving sons, uncles of ‘Abbas Hilmi; the elder of these, Hussein Kamil, was respected by both the British and the Egyptian establishment, and he became Britain's candidate. But he was to prove a hard negotiator: insisting on protecting the hereditary rights of the Muhammad ‘Ali family among other issues. Ronald Storrs in his Memoirs (as the British edition was called; the US edition is called Orientations) tells the story:

A century ago today, the veil came off. Britain declared a protectorate over Egypt, deposed the Khedive and installed his uncle as ruler with the new title of "Sultan," but it was not as simple as that, as there was a month or so of hard bargaining before the deed was done.

|

| Ronald Storrs |

Once Turkey entered the war, there was no question that Britain had to alter the status of Egypt. But to what? In London, many favored outright annexation, making Egypt as much a part of the Empire as India. The Agency in Cairo was alarmed: direct rule would alienate Egyptians and the Muslim world generally, while the policy since 1882 had been to govern through a local ruler. Cheetham and Storrs pleaded for a protectorate instead, On November 19, London agreed, but it took another month before the protectorate was proclaimed.

|

| ‘Abbas Hilmi II |

‘Abbas Hilmi II was the son of the Khedive Tawfiq and grandson of the great Isma‘il, the man who both glorified and bankrupted Egypt the previous century. Isma‘il had two surviving sons, uncles of ‘Abbas Hilmi; the elder of these, Hussein Kamil, was respected by both the British and the Egyptian establishment, and he became Britain's candidate. But he was to prove a hard negotiator: insisting on protecting the hereditary rights of the Muhammad ‘Ali family among other issues. Ronald Storrs in his Memoirs (as the British edition was called; the US edition is called Orientations) tells the story:

But before proclaiming the good news it was necessary to provide the throne with an occupant. Prince Hussein procrastinated in the hope of better terms. The fact of the negotiations was known, and strong family and general pressure was secretly exerted upon him through emissaries from Constantinople to drag on discussions until mid-January by which time the Turks would be ready to attack Egypt and then to break them off. I do not think the Prince was appreciably influenced by this sort of thing, though Harims in those days were almost exclusively Turkish, and domestic pressure, like the Mills of God, though it grind slowly yet grinds exceedingly small. He considered, and I agreed, that he was conferring as well as receiving a favour and that, in the matter of status, his wishes should be met. The Prince was strongly of opinion that Egypt should be transformed into a Kingdom under an Egyptian King. As it was impossible that a vassal prince should bear the same style as his suzerain, I ventured to suggest the alternative of Sultan, an Arab name signifying "the bearer of ruling power" which had been first adopted in Egypt by Saladin, and which was incidentally the title of the ex-Suzerain ruler of the Ottoman Empire. My proposal was accepted by both sides. Majesty being impossible for the same reason as King, Hautesse, the ancient and dignified double of Altesse, was suggested in order to distinguish the sovereign from the spate of obscure and sometimes ignoble collaterals all claiming the title of Highness. Meanwhile, nothing was settled, neither side was committed to anything, and a sharp Allied reverse on any front might plunge us into the dreaded inferiority of hawking round an ever less desirable crown and continually having to offer higher inducement for its acceptance. I had spoken frequently but, as a junior, unofficially, with Prince Hussein, having fresh in my memory the perplexities and humiliations of the Mustafa Fehmy crisis. Negotiations dragged on for about a month. At last the question was narrowed down to the offer by the Government of the throne of Egypt to Prince Hussein with the title of Sultan and - nothing more. The Prince behaved with great dignity, but pointed out that the document contained no mention of heredity in his family or indeed among the descendants of Muhammad Ali; that he, was allowed no voice in the choice of a flag nor was even sure he would have one at all; and that he was not informed whether Egyptians would be British subjects or retain their own entity and nationality under a British Protectorate. I considered him entirely justified on these three points, but we had our instructions, and it seemed impossible to persuade him to accept. The alternative was the proclamation of a Protectorate without any Egyptian Sovereign at all.

Sultan Hussein Kamil

The imposition of the Union Jack, containing as it does the cross in three forms, would have had a bad effect in Egypt and a worse throughout Arabia; and the Khedivial Turkish party, which though dormant still existed, would have been immensely strengthened when it became known that we had not been able to make the rival claimant an offer which his dignity could accept. The Ministers told us frankly that they would not continue in office under a throneless Protectorate. We had given up all hope, and a telegram embodying the Prince's refusal, drafted and typed, lay ready for ciphering on Cheetham's table. As a last resort I primed Shaarawi Pasha, a rich landowner who had been intimate with the Prince all his life, and Ambroise Sinadino, a Greek, in more or less intimate contact with the Agency for the past thirty-five years. They went round independently and as if with no knowledge of the circumstances (I had in fact told them very little) pointed out to Prince Hussein how nervous the country was getting at the prolonged delay in the pro duction of the proclamation, and hoped that the responsibility did not lie on his side, as that might force the English to do things repugnant to them and disastrous to the country. On Sunday evening I received a note from Sinadino. "Mon cher Storrs, J'ai fait de la bonne besogne pendant une heure et demie. Son Altesse aimerait beaucoup avec l'autorisation de Monsieur Cheetham que vous alliez le voir demain lundi avant midi a sa Daira; il pourra ainsi vous parler a coeur ouvert. ]e vous serre la main; bien a vous. Ambroise." I persuaded Cheetham to postpone his final telegram and telephoned to the Prince asking him to see me that evening instead of the next day. He received me very kindly in his Palace at Heliopolis and kept me from 10 till 12. A laconic brevity and a direct coming to the point are not the virtues of Prince Hussein, and he began by quoting a number of instances of his friendliness and loyalty to Great Britain from the very beginning. My soul fainted within me when he described with a wealth of horticultural detail how he had rooted up trees from his own garden at Giza and presented them to the first Lady Cromer and I longed to say: "Monseigneur! passons au Deluge" However, he eventually attacked the subject and speaking without any reserve at all told me that he wanted to accept the Sultanate, but as offered by H.M.G. could not face it. I begged him for his own sake and that of the country to trust the British Government, which had recalled him from exile and which had never yet betrayed him; still he would not accept. At about half-past eleven I said I feared I was intruding upon his leisure, and he asked me whether I would leave with an impresion of an obstinate man: I said No, but with a distinct impression of a Prince who had no confidence in Lord K. or the British Government. He appeared a little staggered at this and said: "I cannot let you go away under this impression; what do you think I had better do?" I recommended him to allow us to put in a strong appeal for the heredity, and to leave the question of the flag and the nationality to the wisdom of the British High Commissioner who was coming out. I pointed out that a Sultan on the throne was in a much better position for bargaining than a claimant however illustrious, and that the Foreign Office, confronted with this notable proof of his bonne volante would be likely to allow him a larger share of confidence and consequently a freer hand in the future. He thought awhile and said: "If you will guarantee that the High Commissioner will decide the other two points in my favour and procure for me the heredity, I accept." I told him that this was not an acceptance at all, but only a post-dating of his demands, that I regretted so small a thing should keep him from doing all the good I knew he would be able to do, but that there was nothing for it now but to dispatch the telegram embodying his refusal. He took leave of me very cordially, and said he very much appreciated my anxiety that the Sultanate should not pass into less worthy hands. I left him at midnight, impressed by his dignity and the real justice of his cause, and informed Cheetham of his offer. Early next morning Prince Hussein sent for the Ministers and, after informing them of what had happened, telephoned to me that he was prepared to accept my suggestion of the night before. He visited Cheetham (who was not a little pleased), withdrew his former refusal and made the new proposal which we have now embodied in a telegram and sent home.At the end of this long saga, Storrs comments:

I have ventured to record thus at length the last inner workings of that rumbling and irregular but beneficent old machine, then about to be thrown on the scrap-heap -- the British "Occupation" of Egypt.So the Khedive became a Sultan, Egypt became a protectorate, and the British Agent/Consul General became a High Commissioner. And the new Sultan did get a new flag and Coat of Arms:

.svg.png) |

| Flag of the Sultanate of Egypt |

Labels:

Egypt,

First World War,

The UK

Something Lighter in a Dark Week

In this week that brought us the horrors of Peshawar, it may be worth a diversion into Ancient Near Eastern Studies humor.

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

Four Years Ago Today, Mohamed Bouazizi Set Himself on Fire...

Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire on December 17, 2010. The flames from the self-immolation of the young street vendor in Tunisia soon spread throughout the Arab world.

Ironically but perhaps fittingly, it is only in Tunisia that the legacy of Arab Spring still offers promise. Egypt has come full circle, actually welcoming military leadership; Syria and Libya are devastated, and Bahrain's spring was cut short. Though Tunisia's two runoff candidates for President are flinging charges at each other, the constitutional process is in play. Good for Tunisia.

|

| Mohamed Bouazizi |

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

Naguib Mahfouz's Widow Has Passed Away

Just days after what would have been Nobel Laureate Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz's 103rd birthday (see here for my post on the 100th three years ago, interviewing his translator and biographer),his widow, Atiyatallah Ibrahim Rizq, has reportedly passed away. (Link is in Arabic).

Mahfouz kept his family life extremely private, and this has received little attention.

Mahfouz kept his family life extremely private, and this has received little attention.

Labels:

Egypt,

Naguib Mahfouz,

obituaries

Hanukkah Greetings

Greetings to my Jewish readers for the first night of Hanukkah, which begins at sundown.

Monday, December 15, 2014

Erdoğan's Ottoman Script Revival and the Legacy of Kemalism

I haven't commented Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announcement last week that he intends to institute the teaching of Ottoman Turkish as a requirement in high schools. Those unfamiliar with the history of Modern Turkey may wonder why the idea of teaching people the language used in the early 20th century is provoking a backlash in Turkey.

It is not just a sign of Erdoğan's "neo-Ottoman" proclivities as well as his continuing efforts to dismantle the secular "laicist" aspects of Turkish society; it is also one of his most direct assaults to date on the Kemalist legacy.

Of all of Kemal Atatürk's reforms aimed at radically transforming Turkey — abolition of the Sultanate and Caliphate, declaring the republic, instituting secularism and a Western work week, adoption of regularized surnames, banning traditional headgear like the fez and the veil — perhaps none more thoroughly undercut traditional Ottoman ways more than the language reform of 1928, which abandoned the Arabic/Persian script used to write Ottoman Turkish and adopted a modified Latin script. At the same time and after (with the founding of the Turkish Language Association in 1932), efforts were made to purge the language of the large vocabulary of Arabic and Persian loanwords and to replace them with Turkic words.

The Kemalist reforms made much linguistic sense: Turkish is an agglutinative language in which vowel harmony plays a major role, but the Arabic script is usually written with few or no vowels. But the other side of the reform was to cut modern Turks off from their heritage; only scholars and historians still learned Ottoman, so most Turks could not read materials written before 1928 unless they were transcribed into Modern Turkish.

So by seeking to require the teaching of Ottoman and the Arabic-Persian script in secondary schools, Erdoğan is directly attempting to reverse perhaps the most sweeping of the Kemalist reforms and thus the whole Kemalist legacy, which he has been chipping away at as long as the AKP has been in power.

It is not just a sign of Erdoğan's "neo-Ottoman" proclivities as well as his continuing efforts to dismantle the secular "laicist" aspects of Turkish society; it is also one of his most direct assaults to date on the Kemalist legacy.

Of all of Kemal Atatürk's reforms aimed at radically transforming Turkey — abolition of the Sultanate and Caliphate, declaring the republic, instituting secularism and a Western work week, adoption of regularized surnames, banning traditional headgear like the fez and the veil — perhaps none more thoroughly undercut traditional Ottoman ways more than the language reform of 1928, which abandoned the Arabic/Persian script used to write Ottoman Turkish and adopted a modified Latin script. At the same time and after (with the founding of the Turkish Language Association in 1932), efforts were made to purge the language of the large vocabulary of Arabic and Persian loanwords and to replace them with Turkic words.

The Kemalist reforms made much linguistic sense: Turkish is an agglutinative language in which vowel harmony plays a major role, but the Arabic script is usually written with few or no vowels. But the other side of the reform was to cut modern Turks off from their heritage; only scholars and historians still learned Ottoman, so most Turks could not read materials written before 1928 unless they were transcribed into Modern Turkish.

So by seeking to require the teaching of Ottoman and the Arabic-Persian script in secondary schools, Erdoğan is directly attempting to reverse perhaps the most sweeping of the Kemalist reforms and thus the whole Kemalist legacy, which he has been chipping away at as long as the AKP has been in power.

Labels:

Turkey,

Turkish language

Haaretz on "The Forgotten Jews of Sudan"

Haaretz' title sums it up: "The forgotten Jews of Sudan even researchers haven't heard of."

Excerpt:

Excerpt:

In its heyday, the Jewish community in Sudan had fewer than 1,000 members – a drop in the sea compared to the 260,000-strong Moroccan-Jewish community, the 135,000-strong Algerian community, the 125,000 Jews living in Iraq, the 90,000-strong Tunisian community, and the 75,000 Jews who lived in Egypt before Israel was established.

The Jewish community in Sudan dissolved after 1956, when the country became independent and joined the Arab League. An estimated 500 Jews came to Israel, while the rest dispersed around the world.

Friday, December 12, 2014

December 13, 1914: Submarine HMS B11 Sinks Turkey's Mesudiye in the Dardanelles

|

| A fanciful portrayal as B11 was submerged |

It looked nothing like the fanciful sketch above, however, since His Majesty's Submarine B11 remained submerged at periscope depth throughout the entire attack

The achievement earned for the 26-year-old Lieutenant Holbrook the first Victoria Cross ever awarded to a submariner, and the first naval VC of the war. The VC is of course Britain's highest military honor.

|

| Holbrook souvenir card |

|

| Scale model of HMS B11 in Holbrook, NSW |

|

| Mesudiye after her refit |

Mesudiye was old (launched in 1874) after being built, ironically given her ultimate fate, at the Thames Iron Works in Britain. She was originally rated as a central-battery ironclad. In 1903 she was sent to Genoa for a complete rebuild and refit, and was subsequently classed as a pre-Dreadnought battleship, though her tonnage was less than half of that of the modern battle cruiser Yavuz (ex-Goeben). Worse still, her two big central guns had never been installed.

|

| B11, decks awash |

Here's a period newspaper illustration; the narrative of the battle follows below.

Let's begin with the British side first. From the History of the Great War - Naval Operations, Volune 2, by Sir Julian Corbett (himself a distinguished sea power theorist), we find the details of Lieutenant Holbrook's attack:

It may be worth mentioning that B11 was operated by a crew of two officers and 11 men. In these early days of submarine warfare, it is worth noting how frequently the accounts note with some wonder that B11 remained submerged for nine hours. At this time surface vessels had no sonar and no way of detecting submarines unless they spotted the periscope. Even if spotted, they had no depth charges, while the sub had the torpedo.So great was the demand for destroyers at home to meet the submarine menace that he [Admiral Carden] was only allowed to keep the six he had on his urgent representation that the six boats the French had sent were of too old a type to deal with the modern Turkish ones. The Goeben moreover was soon active again. From December 7 to 10 she had been out in the Black Sea with the Hamidieh escorting troops and transports, and had bombarded Batum for a short time. At the same time the Breslau had been detected apparently laying mines off Sevastopol, but had been met by bombing aeroplanes. In the Dardanelles was another cruiser, the Messudieh, guarding the minefield below the Narrows. Without more cruisers it was therefore impossible to maintain a blockade of Smyrna and Dedeagatch, and at the same time guard the flying base which had been established for the flotilla at Port Sigri, in Mityleni. The French, however, came to the rescue by sending up two ships, the cruiser Amiral Charner and the seaplane carrier Foudre, which, having left her sea-planes in Egypt, had been doing escort duty on the Port Said-Malta line. They were still on their way when a brilliant piece of service was performed, which did something to relieve the Admiral's anxiety and much to brighten the monotony of the eventless vigil.For some time the three British submarines (B.9, 10 and 11) and the three French, had been itching for a new experience. There were known to be five lines of mines across the fairway inside the Straits, but Captain C. P. R. Coode, the resourceful commander of the destroyer flotilla, and Lieutenant-Commander G. H. Pownall, who commanded the submarines under him, believed that by fitting a submarine with certain guards the obstacle could be passed. Amongst both the French and the British submarine commanders there was keen competition to be made the subject of the experiment. Eventually the choice fell on Lieutenant N. D. Holbrook, of B.11, which had recently had her batteries renewed and had already been two miles up the Straits in chase of two Turkish gunboats.On December 13, having been duly fitted with guards, she went in to torpedo anything she could get at. In spite of the strong adverse current Lieutenant Holbrook succeeded in taking his boat clear under the five rows of mines, and, sighting a large two-funnelled vessel painted grey with the Turkish ensign flying, he closed her to 800 yards, fired a torpedo and immediately dived. As the submarine dipped he heard the explosion, and putting up his periscope saw that the vessel was settling by the stern. He had now to make the return journey, but to the danger of the mine-field a fresh peril was added; the lenses of the compass had become so badly fogged, that steering by it was no longer possible. He was not even sure where he was, but taking into consideration the time since he had passed Cape Helles, and the fact that the boat appeared to be entirely surrounded by land, he calculated that he must be in Sari Sighlar Bay.Several times he bumped the bottom as he ran along submerged at full speed, but the risk of ripping open the submarine had to be taken, and it was not till half an hour had passed and be judged that the mines must now be behind him that he put up his periscope again. There was now a clear horizon on his port beam, and for this he steered, taking peeps from time to time to correct his course since the compass was still unserviceable. Our watching destroyers noticed a torpedo-boat apparently searching for him; but after he had dived twice under a minefield and navigated the Dardanelles submerged without a compass, so ordinary a hazard seems to have escaped his notice. It was not till he returned to the base, having been nine hours under water, that he learned that the vessel he had torpedoed was the cruiser Messudieh. Such an exploit was quite without precedent. The Admiralty at once telegraphed their highest appreciation of the resource and daring displayed. Lieutenant Holbrook received the V.C, Lieutenant S. T. Winn, his second in command, a D.S.O., and every member of the crew a D.S.C. or D.S.M. according to rank. (The Turks state that the Messudieh was placed in this exposed position by the Germans contrary to Turkish opinion. They also say she was hit before she saw the submarine or could open fire, and that she turned over and sank in ten minutes. Many men were imprisoned in her, but most of them were extricated, when plant and divers arrived from Constantinople and holes could be cut in her bottom. In all 49 officers and 587 men were saved. The casualties were 10 officers and 27 men killed. She sank in shoal water and most of her guns were afterwards salved and added to the minefield and intermediate defences.)Encouraged by this success Admiral Carden asked for one of the latest class of submarines. He was sure that if fitted like B.11 she could go right up to the Golden Horn. But as the Scarborough raid had just taken place and the High Seas Fleet showed signs of awakening none could be spared, and the blockade settled down again to its dull routine. Though there were constant rumours of a coming destroyer attack in retaliation for the loss of the Messudieh, the indications were that at the Dardanelles the enemy's only thought was defence.

|

| Mesudiye after sinking |

The Allies were planning first to cross the straits with submarines, which would make the warships’ job easier in the subsequent phases of the war. However, crossing the straits was not an easy job, not only because of the mine barrages, coastal barriers, observers and projectors, but also because of the strong currents and differences in water density. The first Allied submarine to be sighted by the Turks was the French Faradi, which, on November 23, approached the entrance of the Dardanelles, but had to retreat as the Turkish batteries at Seddülbahir opened fire. A few days later, the British submarine B-11, commanded by Lt Cmd Norman Holbrook was given the task to attempt to force the Dardanelles.B-11 set sail from Tenedos during the early hours of December 13, 1914. Successfully passing under five mine barrages, she arrived at the Sarısığlar Bay where she sighted Mesudiye at around 11:30 am. B-11 fired two torpedoes. Mesudiye immediately opened fire with her remaining guns, but this was to no avail. In ten minutes the battleship capsized and sank in shallow water. In his memoirs, Captain Üsküdarlı Rıfat Bey, who was the acting commander of Mesudiye at the time of the attack, wrote about the details of the event: “There was no point in continuing to fire. I had to think about the personnel, so I ordered ceasefire to be followed by an order to leave the ship. The first torpedo of the enemy submarine hit a little above the ammunition storage of Mesudiye’s stern guns. If it were only 15-20 cm below, it would be a direct hit on the ammunition storage and the ship would blow up in the instant. We had replaced the removed guns with sand and chains in order to keep the balance. If that had not been done, the ammunition storage would be elevated and that would result in a direct hit.”

As B-11 returned to its base, the Turkish transport Bolayır rescued 48 officers and 573 men from Mesudiye. Some sailors were trapped inside the ship and it took 36 hours to release them. Total Turkish losses were 34, including ten officers and 24 men. The guns salvaged from Mesudiye were installed at a coastal battery named after the ship itself.The loss of Mesudiye was a psychological blow for the Turks, which forced them to strengthen the defenses of the Dardanelles. New mine barrages were erected by Samsun and Nusrat. By the end of 1914, there were nine lines comprising of a total of 324 mines inside the Dardanelles. On the Allied side, encouraged by B-11’s success, Vice Admiral Sackville Carden asked for more submarines to be deployed in the area, although his request could only be fulfilled to a limited extent by the Admiralty. Carden also decreed that no Allied submarine would sail on patrol without his express permission.

|

| Holbrook |

Even the sunken Mesudiye would have a measure of revenge. As the accounts above note, one reason that so many were rescued was that it went down in shoal-depth. As a result, her guns were also salvaged, and they were installed ashore in a shore battery also named Mesudiye.

|

| Mesudiye's Guns' Revenge: Bouvet sinking, March 1915 |

At least one of her guns is still reportedly on display at Gallipoli (left).

Labels:

Australia,

First World War,

Ottoman Empire,

The UK,

Turkey

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)